Last year ESET published a blogpost about AceCryptor – one of the most popular and prevalent cryptors-as-a-service (CaaS) operating since 2016. For H1 2023 we published statistics from our telemetry, according to which trends from previous periods continued without drastic changes.

However, in H2 2023 we registered a significant change in how AceCryptor is used. Not only we have seen and blocked over double the attacks in H2 2023 in comparison with H1 2023, but we also noticed that Rescoms (also known as Remcos) started using AceCryptor, which was not the case beforehand.

The vast majority of AceCryptor-packed Rescoms RAT samples were used as an initial compromise vector in multiple spam campaigns targeting European countries including Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Serbia.

Key points of this blogpost:

- AceCryptor continued to provide packing services to tens of very well-known malware families in H2 2023.

- Even though well known by security products, AceCryptor’s prevalence is not showing indications of decline: on the contrary, the number of attacks significantly increased due to the Rescoms campaigns.

- AceCryptor is a cryptor of choice of threat actors targeting specific countries and targets (e.g., companies in a particular country).

- In H2 2023, ESET detected multiple AceCryptor+Rescoms campaigns in European countries, mainly Poland, Bulgaria, Spain, and Serbia.

- The threat actor behind those campaigns in some cases abused compromised accounts to send spam emails in order to make them look as credible as possible.

- The goal of the spam campaigns was to obtain credentials stored in browsers or email clients, which in case of a successful compromise would open possibilities for further attacks.

AceCryptor in H2 2023

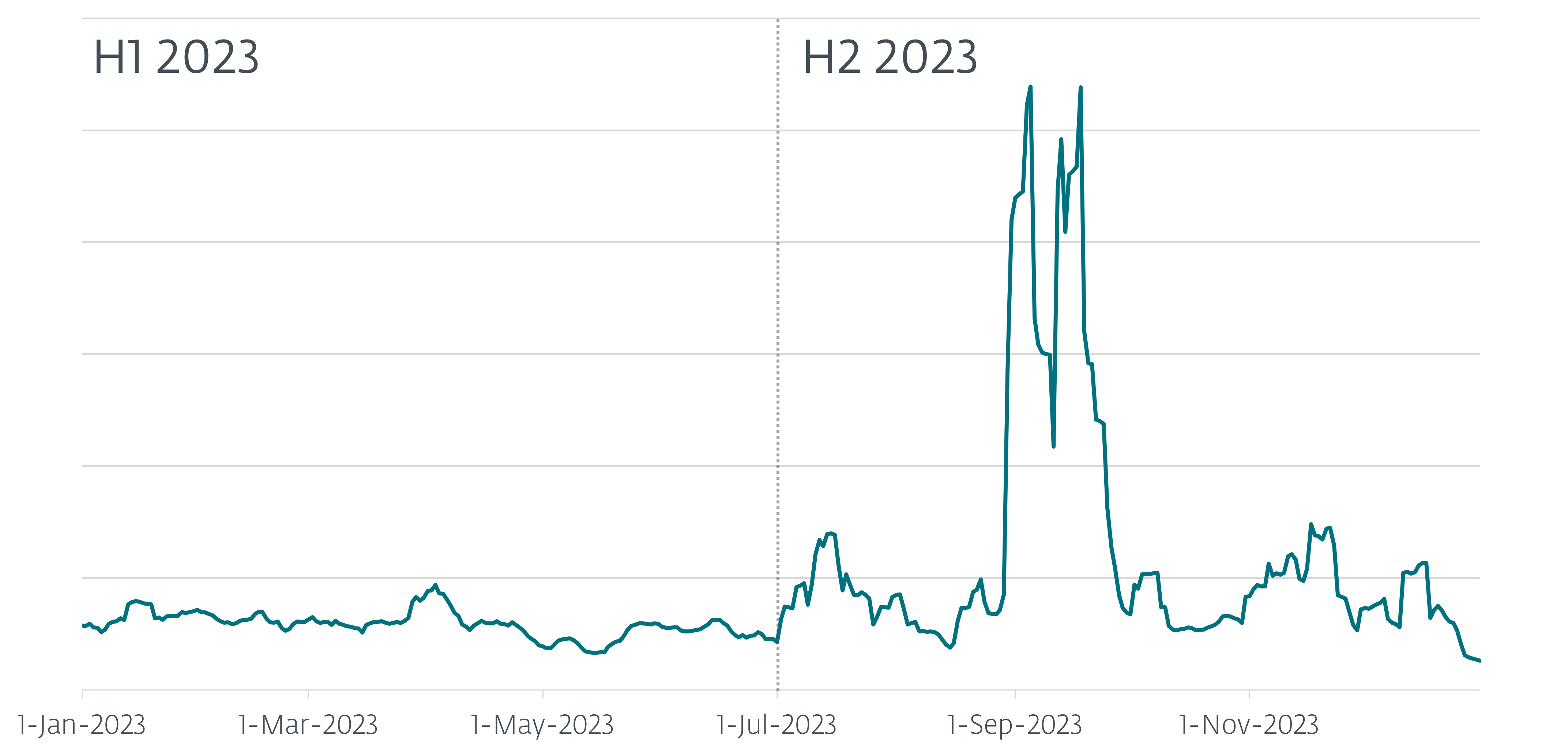

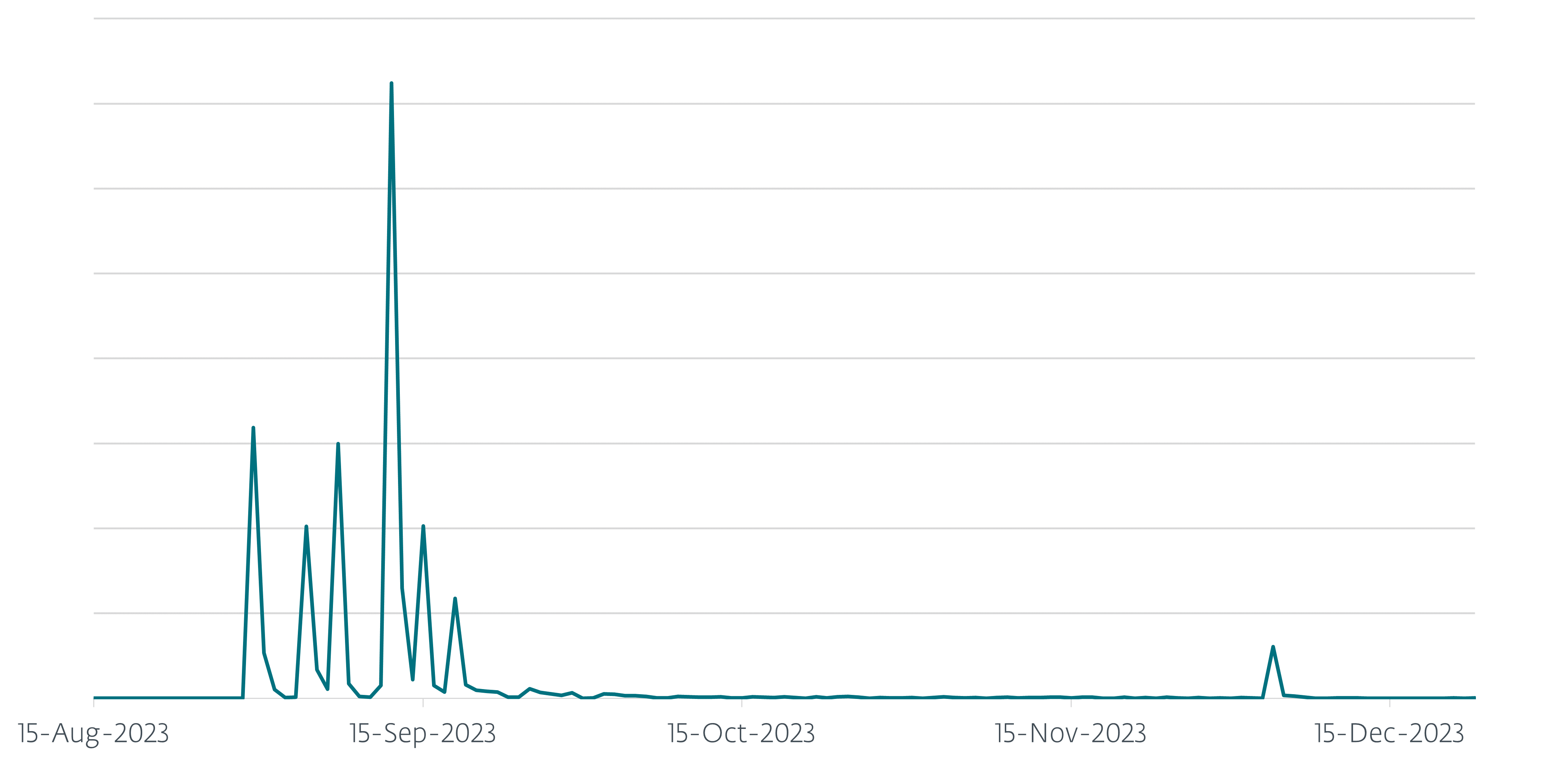

In the first half of 2023 ESET protected around 13,000 users from AceCryptor-packed malware. In the second half of the year, there was a massive increase of AceCryptor-packed malware spreading in the wild, with our detections tripling, resulting in over 42,000 protected ESET users worldwide. As can be observed in Figure 1, we detected multiple sudden waves of malware spreading. These spikes show multiple spam campaigns targeted at European countries where AceCryptor packed a Rescoms RAT (discussed more in the Rescoms campaigns section).

Furthermore, when we compare the raw number of samples: in the first half of 2023, ESET detected over 23,000 unique malicious samples of AceCryptor; in the second half of 2023, we saw and detected “only” over 17,000 unique samples. Even though this might be unexpected, after a closer look at the data there is a reasonable explanation. The Rescoms spam campaigns used the same malicious file(s) in email campaigns sent to a greater number of users, thus increasing the number of people who encountered the malware, but still keeping the number of different files low. This did not happen in previous periods as Rescoms was almost never used in combination with AceCryptor. Another reason for the decrement in the number of unique samples is because some popular families apparently stopped (or almost stopped) using AceCryptor as their go-to CaaS. An example is Danabot malware which stopped using AceCryptor; also, the prominent RedLine Stealer whose users stopped using AceCryptor as much, based on a greater than 60% decrease in AceCryptor samples containing that malware.

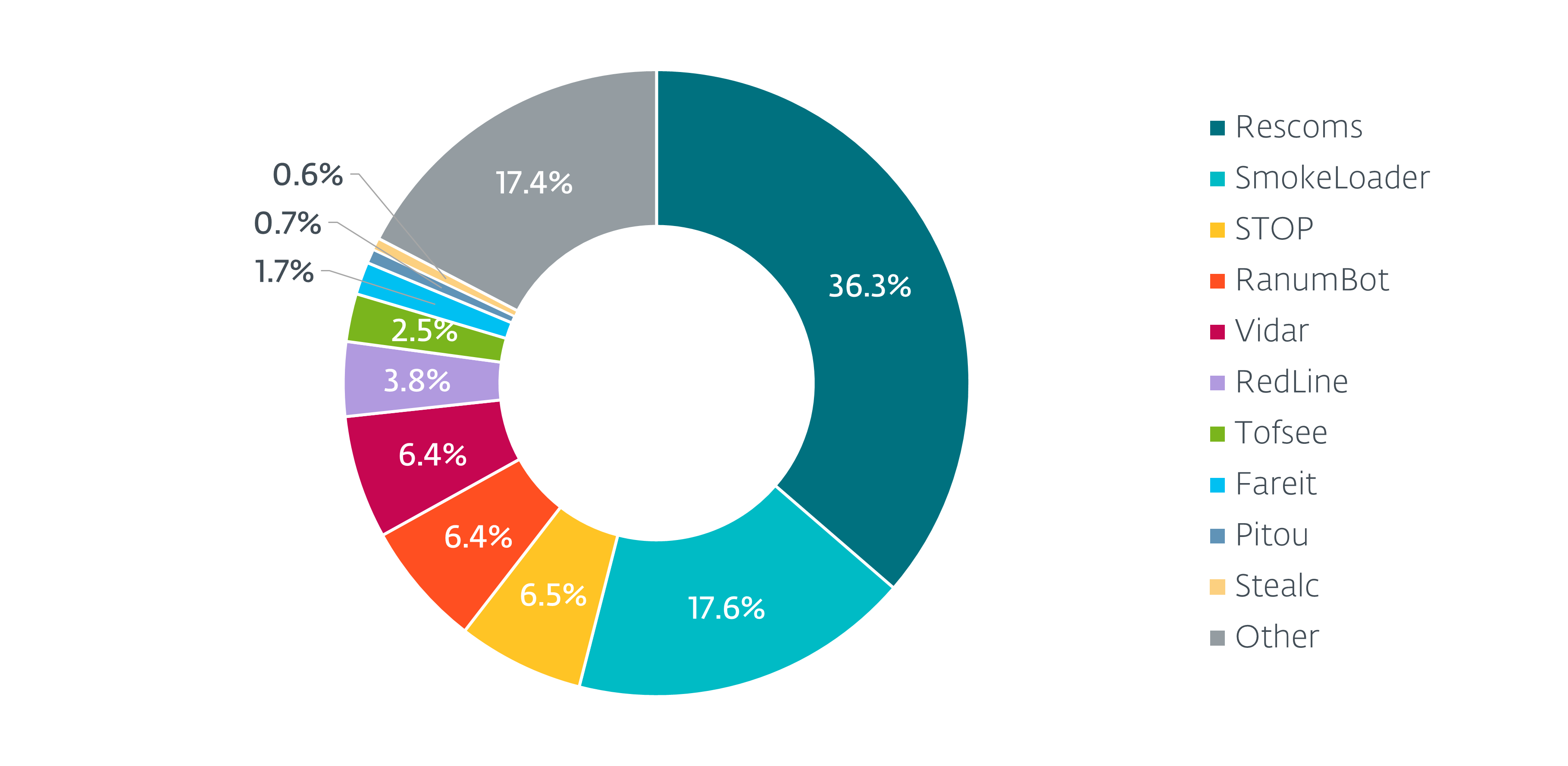

As seen in Figure 2, AceCryptor still distributes, apart from Rescoms, samples from many different malware families, such as SmokeLoader, STOP ransomware, and Vidar stealer.

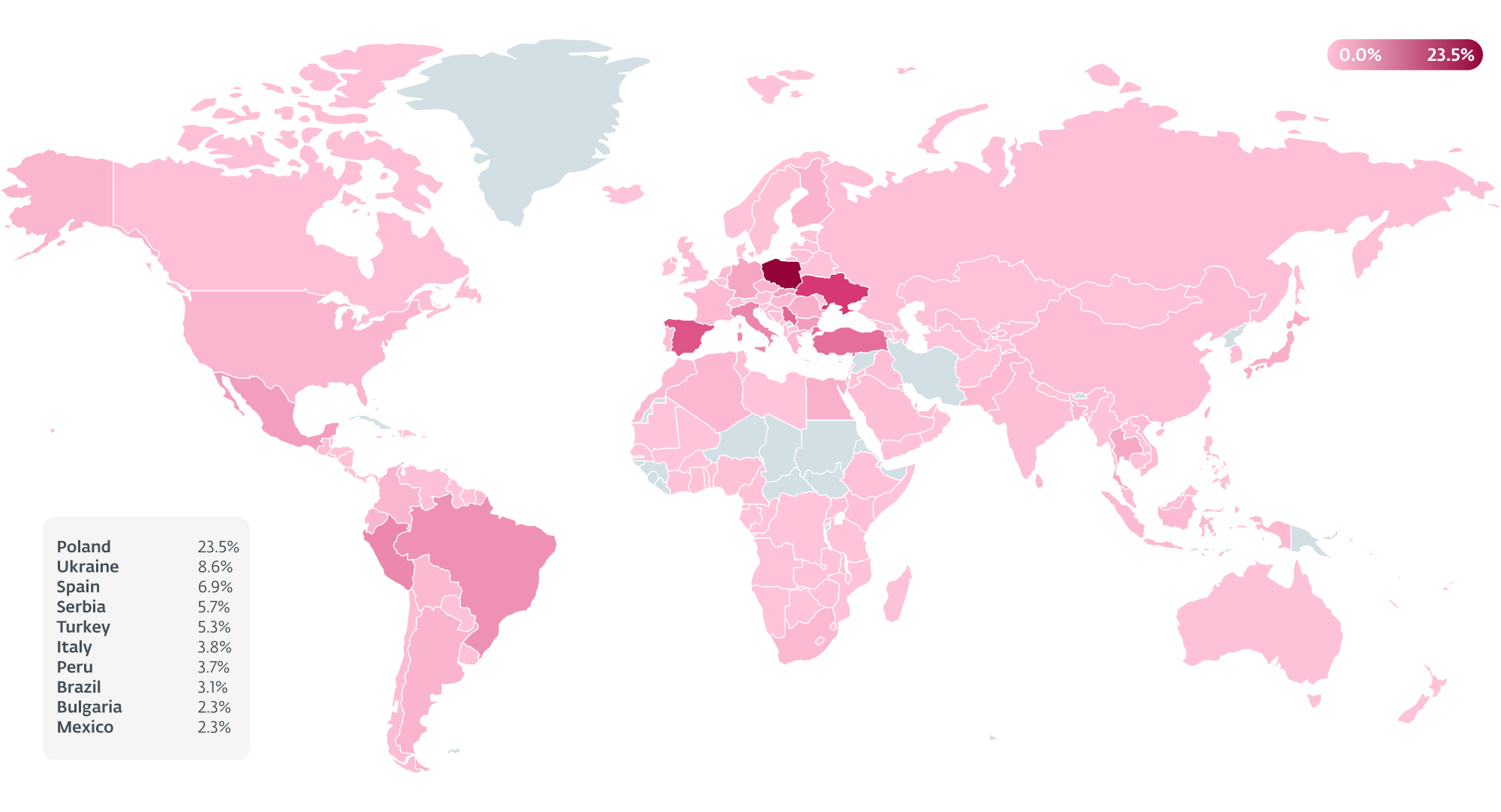

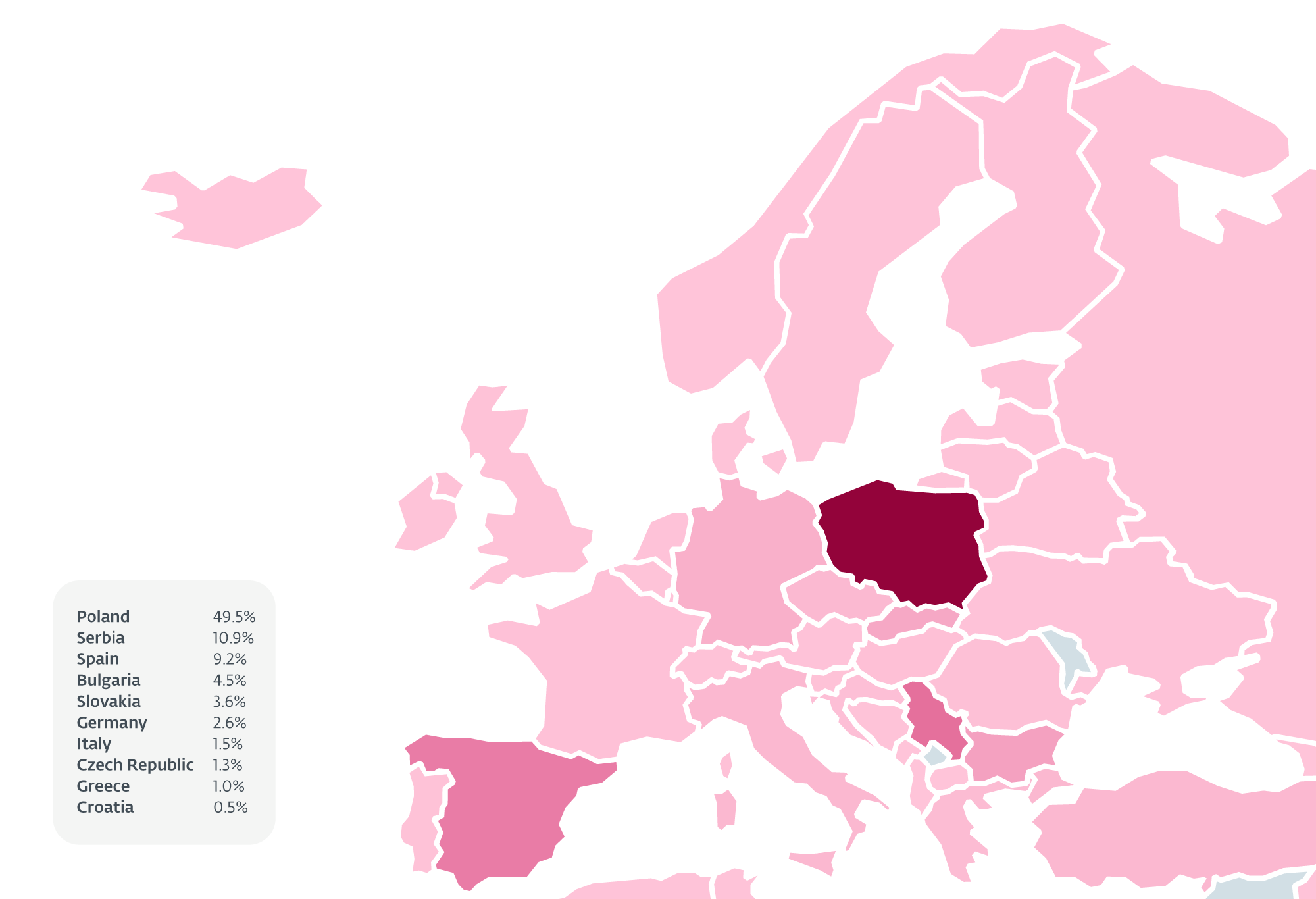

In the first half of 2023, the countries most affected by malware packed by AceCryptor were Peru, Mexico, Egypt, and Türkiye, where Peru, at 4,700, had the greatest number of attacks. Rescoms spam campaigns changed these statistics dramatically in the second half of the year. As can be seen in Figure 3, AceCryptor-packed malware affected mostly European countries. By far the most affected country is Poland, where ESET prevented over 26,000 attacks; this is followed by Ukraine, Spain, and Serbia. And, it’s worth mentioning that in each of those countries ESET products prevented more attacks than in the most affected country in H1 2023, Peru.

AceCryptor samples that we’ve observed in H2 often contained two malware families as their payload: Rescoms and SmokeLoader. A spike in Ukraine was caused by SmokeLoader. This fact was already mentioned by Ukraine’s NSDC. On the other hand, in Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Serbia the increased activity was caused by AceCryptor containing Rescoms as a final payload.

Rescoms campaigns

In the first half of 2023, we saw in our telemetry fewer than a hundred incidents of AceCryptor samples with Rescoms inside. During the second half of the year, Rescoms became the most prevalent malware family packed by AceCryptor, with over 32,000 hits. Over half of these attempts happened in Poland, followed by Serbia, Spain, Bulgaria, and Slovakia (Figure 4).

Campaigns in Poland

Thanks to ESET telemetry we’ve been able to observe eight significant spam campaigns targeting Poland in H2 2023. As can be seen in Figure 5, the majority of them happened in September, but there were also campaigns in August and December.

In total, ESET registered over 26,000 of these attacks in Poland for this period. All spam campaigns targeted businesses in Poland and all emails had very similar subject lines about B2B offers for the victim companies. To look as believable as possible, the attackers incorporated the following tricks into the spam emails:

- Email addresses they were sending spam emails from imitated domains of other companies. Attackers used a different TLD, changed a letter in a company name or the word order in the case of a multi-word company name (this technique is known as typosquatting).

- The most noteworthy is that multiple campaigns involved business email compromise – attackers abused previously compromised email accounts of other company employees to send spam emails. In this way even if the potential victim looked for the usual red flags, they were just not there, and the email looked as legitimate as it could have.

Attackers did their research and used existing Polish company names and even existing employee/owner names and contact information when signing those emails. This was done so that in the case where a victim tries to Google the sender’s name, the search would be successful, which might lead them to open the malicious attachment.

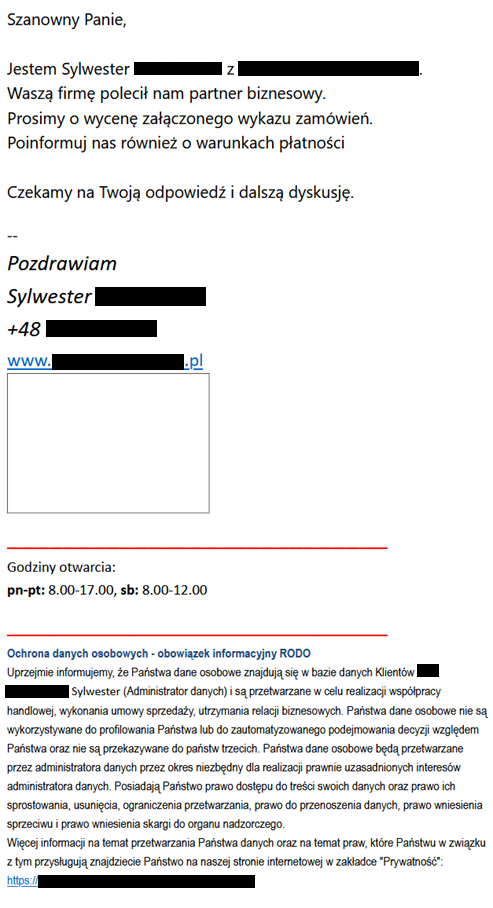

- The content of spam emails was in some cases simpler but in many cases (like the example in Figure 6) quite elaborate. Especially these more elaborate versions should be considered dangerous as they deviate from the standard pattern of generic text, which is often riddled with grammatical mistakes.

The email shown in Figure 6 contains a message followed by information about the processing of personal information done by the alleged sender and the possibility to “access the content of your data and the right to rectify, delete, limit processing restrictions, right to data transfer, right to raise an objection, and the right to lodge a complaint with the supervisory authority”. The message itself can be translated thus:

Dear Sir,

I am Sylwester [redacted] from [redacted]. Your company was recommended to us by a business partner. Please quote the attached order list. Please also inform us about the payment terms.

We look forward to your response and further discussion.

--

Best Regards,

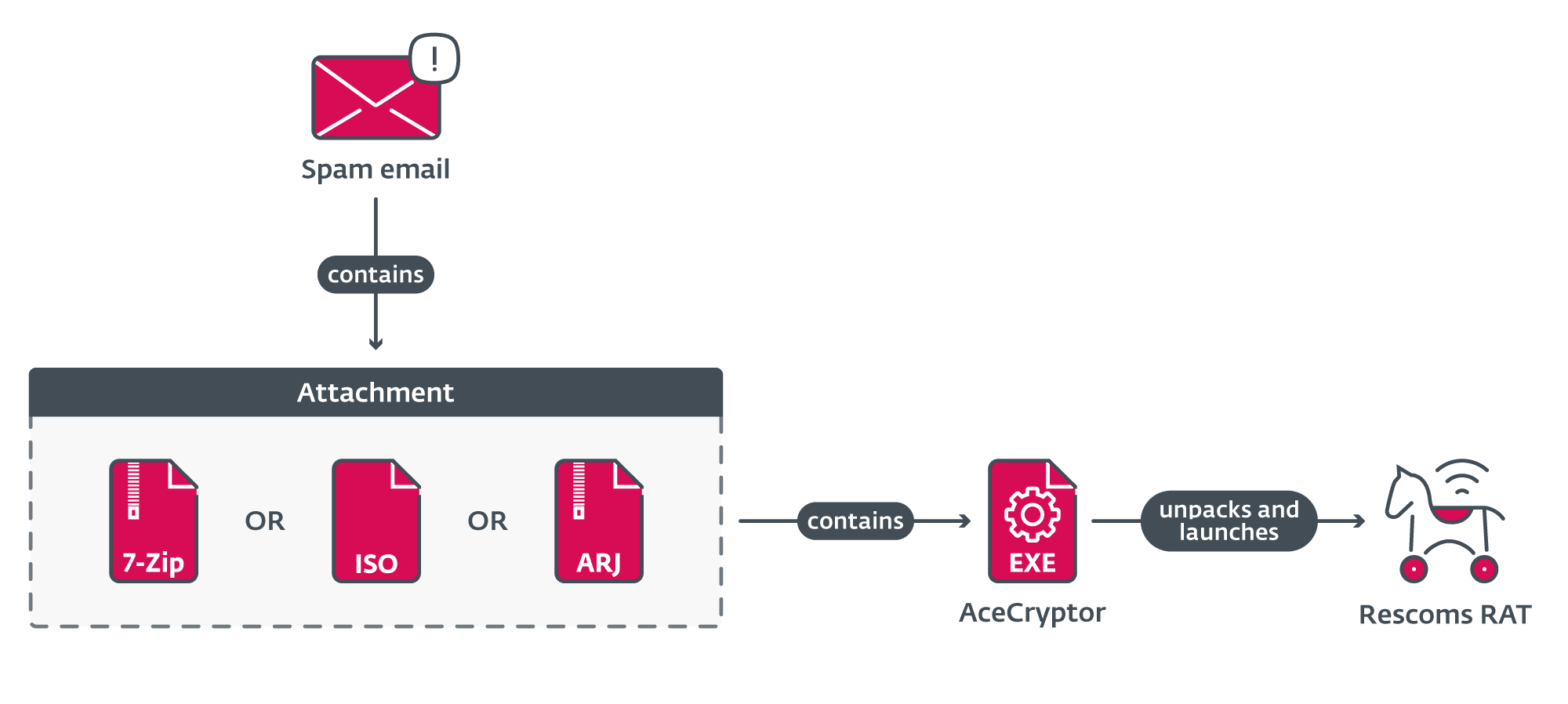

Attachments in all campaigns looked quite similar (Figure 7). Emails contained an attached archive or ISO file named offer/inquiry (of course in Polish), in some cases also accompanied with an order number. That file contained an AceCryptor executable that unpacked and launched Rescoms.

Based on the behavior of the malware, we assume that the goal of these campaigns was to obtain email and browser credentials, and thus gain initial access to the targeted companies. While it is unknown whether the credentials were gathered for the group that carried out these attacks or if those stolen credentials would be later sold to other threat actors, it is certain that successful compromise opens the possibility for further attacks, especially from, currently popular, ransomware attacks.

It is important to state that Rescoms RAT can be bought; thus many threat actors use it in their operations. These campaigns are not only connected by target similarity, attachment structure, email text, or tricks and techniques used to deceive potential victims, but also by some less obvious properties. In the malware itself, we were able to find artifacts (e.g., the license ID for Rescoms) that tie those campaigns together, revealing that many of these attacks were carried out by one threat actor.

Campaigns in Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Serbia

During the same time periods as the campaigns in Poland, ESET telemetry also registered ongoing campaigns in Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Serbia. These campaigns also mainly targeted local companies and we can even find artifacts in the malware itself tying these campaigns to the same threat actor that carried out the campaigns in Poland. The only significant thing that changed was, of course, the language used in the spam emails to be suitable for those specific countries.

Campaigns in Spain

Apart from previously mentioned campaigns, Spain also experienced a surge of spam emails with Rescoms as the final payload. Even though we can confirm that at least one of the campaigns was carried out by the same threat actor as in these previous cases, other campaigns followed a somewhat different pattern. Furthermore, even artifacts that were the same in previous cases differed in these and, because of that, we cannot conclude that the campaigns in Spain originated from the same place.

Conclusion

During the second half of 2023 we detected a shift in the usage of AceCryptor – a popular cryptor used by multiple threat actors to pack many malware families. Even though the prevalence of some malware families like RedLine Stealer dropped, other threat actors started using it or used it even more for their activities and AceCryptor is still going strong.In these campaigns AceCryptor was used to target multiple European countries, and to extract information or gain initial access to multiple companies. Malware in these attacks was distributed in spam emails, which were in some cases quite convincing; sometimes the spam was even sent from legitimate, but abused email accounts. Because opening attachments from such emails can have severe consequences for you or your company, we advise that you be aware about what you are opening and use reliable endpoint security software able to detect the malware.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.

ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

IoCs

A comprehensive list of Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) can be found in our GitHub repository.

Files

|

SHA-1 |

Filename |

Detection |

Description |

|

7D99E7AD21B54F07E857 |

PR18213.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HVOB |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Serbia during December 2023. |

|

7DB6780A1E09AEC6146E |

zapytanie.7z |

Win32/Kryptik.HUNX |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during September 2023. |

|

7ED3EFDA8FC446182792 |

20230904104100858.7z |

Win32/Kryptik.HUMX |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland and Bulgaria during September 2023. |

|

9A6C731E96572399B236 |

20230904114635180.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HUMX |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Serbia during September 2023. |

|

57E4EB244F3450854E5B |

SA092300102.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HUPK |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Bulgaria during September 2023. |

|

178C054C5370E0DC9DF8 |

zamowienie_135200.7z |

Win32/Kryptik.HUMI |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during August 2023. |

|

394CFA4150E7D47BBDA1 |

PRV23_8401.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HUMF |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Serbia during August 2023. |

|

3734BC2D9C321604FEA1 |

BP_50C55_20230 |

Win32/Kryptik.HUMF |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Bulgaria during August 2023. |

|

71076BD712C2E3BC8CA5 |

20_J402_MRO_EMS |

Win32/Rescoms.B |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Slovakia during August 2023. |

|

667133FEBA54801B0881 |

7360_37763.iso |

Win32/Rescoms.B |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Bulgaria during December 2023. |

|

AF021E767E68F6CE1D20 |

zapytanie ofertowe.7z |

Win32/Kryptik.HUQF |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during September 2023. |

|

BB6A9FB0C5DA4972EFAB |

129550.7z |

Win32/Kryptik.HUNC |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during September 2023. |

|

D2FF84892F3A4E4436BE |

Zamowienie_ andre.7z |

Win32/Kryptik.HUOZ |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during September 2023. |

|

DB87AA88F358D9517EEB |

20030703_S1002.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HUNI |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Serbia during September 2023. |

|

EF2106A0A40BB5C1A74A |

Zamowienie_830.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HVOB |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during December 2023. |

|

FAD97EC6447A699179B0 |

lista zamówień i szczegółowe zdjęcia.arj |

Win32/Kryptik.HUPK |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Poland during September 2023. |

|

FB8F64D2FEC152D2D135 |

Pedido.iso |

Win32/Kryptik.HUMF |

Malicious attachment from spam campaign carried out in Spain during August 2023. |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This table was built using version 14 of the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

|

Tactic |

ID |

Name |

Description |

|

Reconnaissance |

Gather Victim Identity Information: Email Addresses |

Email addresses and contact information (either bought or gathered from publicly available sources) were used in phishing campaigns to target companies across multiple countries. |

|

|

Resource Development |

Compromise Accounts: Email Accounts |

Attackers used compromised email accounts to send phishing emails in spam campaigns to increase spam email’s credibility. |

|

|

Obtain Capabilities: Malware |

Attackers bought and used AceCryptor and Rescoms for phishing campaigns. |

||

|

Initial Access |

Phishing |

Attackers used phishing messages with malicious attachments to compromise computers and steal information from companies in multiple European countries. |

|

|

Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment |

Attackers used spearphishing messages to compromise computers and steal information from companies in multiple European countries. |

||

|

Execution |

User Execution: Malicious File |

Attackers relied on users opening and launching malicious files with malware packed by AceCryptor. |

|

|

Credential Access |

Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers |

Attackers tried to steal credential information from browsers and email clients. |