On January 14th this year, a raid by Russian law enforcement authorities made headlines all over the world, as it resulted in the arrests of 14 members of the infamous Sodinokibi/REvil ransomware gang. The crackdown came after a series of talks between U.S. and Russian officials, including June’s Geneva meeting between Presidents Biden and Putin. The Russian intelligence agency, FSB, confirmed that “the individual responsible for the attack on Colonial Pipeline last spring” was arrested as part of the raid.

At the time, when a Russian invasion of Ukraine was a real possibility, some saw this development as a “huge result that few would expect.” Others even called it “Russian ransomware diplomacy”, a kind of message to the U.S. about how far Russia was willing to go in exchange for lighter sanctions over a future invasion of Ukraine.

RELATED READING: ESET Research webinar: How APT groups have turned Ukraine into a cyber‑battlefield

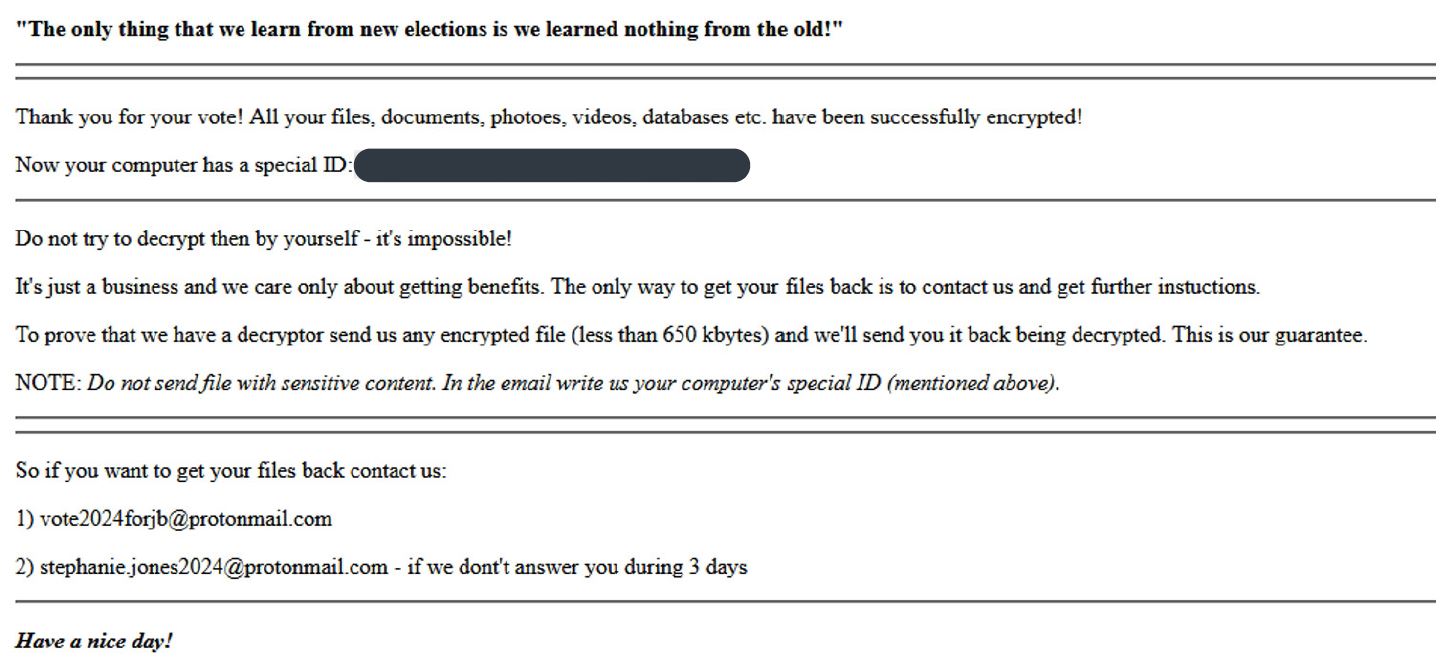

The night before (on January 13th, Orthodox New Year’s Eve), a number of Ukraine’s government agencies, NGOs and IT organizations were targeted by WhisperGate, destructive malware that, according to Microsoft, was “designed to look like ransomware but lacking a ransom recovery mechanism”. This kind of faux ransomware, as ESET researchers also categorize it, has the ultimate goal of making the targeted devices inoperable, thus suggesting their connection with nation-state actors, rather than with cybercrime gangs.

On January 14th, the websites of multiple Ukrainian ministries and government agencies were defaced to display anti-Ukraine imagery and a message reading, “Be afraid and fear the worst”. Both government and private entities kept being targeted in the days ahead of the invasion, including by a series of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that knocked out several important websites in Ukraine. At the same time, the clients of a major Ukrainian bank were on the receiving end of an SMS campaign that alerted them of fake disruptions of the bank’s ATM network.

Barely an hour before the invasion, a major cyberattack at Viasat’s satellite KA-SAT disrupted broadband internet service for thousands of Ukrainians as well as other European customers, leaving behind thousands of bricked modems. Both the US and the EU condemned the attack and attributed it to Russia, who they believe intended to impair the communication capabilities of the Ukrainian command during the first hours of the invasion.

The first hours

The attacks did not stop there. On the contrary, the cyber-incursions in January and early February were just a prelude to what was about to come. On the evening of February 23rd, following the DDoS attacks that brought several vital Ukrainian websites offline, ESET detected new data-wiping malware – HermeticWiper – on hundreds of machines in several organizations in Ukraine. The wiper’s time stamp, meanwhile, shows that the malware was compiled on December 28th, 2021, suggesting the attack may have been in the works for some time.

The next day, while the military invasion of Ukraine was unfolding, ESET researchers spotted yet more data-wiping malware on Ukrainian systems. IssacWiper was far less sophisticated than, and had no code similarity with, HermeticWiper, and was ultimately less successful in wiping the data on targeted machines.

In a much smaller deployment, ESET researchers also observed HermeticRansom being used at the same time as HermeticWiper. HermeticRansom was first reported in the early hours of February 24th and is faux ransomware. In other words, it had no financial motives and was instead deployed as a decoy while the wiper did the damage.

The next 99 days

ESET researchers believe that the various data wiping attacks, including those involving CaddyWiper, which was discovered March 14th, were intended to target specific organizations with the aim of impairing their ability to respond adequately to the invasion. ESET identified victims in the financial, media and government sectors and attributed both HermeticWiper and CaddyWiper to Sandworm, a group identified by the U.S. as being part of Russia's GRU military intelligence agency.

The same infamous group was also responsible for attempting to deploy Industroyer2 against a high-voltage electrical substation in Ukraine, a discovery made in time thanks to collaboration between ESET and CERT-UA. The malware is a new version of Industroyer, the dangerous malware used to attack the Ukrainian electric power grid back in 2016, leaving thousands of people without electricity.

Several other campaigns went on, including DDoS attacks, malware compromising media networks, NGOs and telecom providers, and government entities. The Russian invasion of Ukraine had sizable influence on the ransomware landscape and not only in Ukraine.

A taste of its own medicine

In the first few months of 2022, according to ESET telemetry, Russia was the top targeted country for all ransomware attacks, with 12% of total detections. This development is in stark contrast to the situation before the invasion, when Russia and some members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) avoided many ransomware attacks, probably due to criminals residing in those countries or fearing Russia’s retribution.

Some of the attacks were directed at Russian entities, including the space agency Roscosmos and the state-owned TV and radio network VGTRK. The attacks at Roscosmos and VGTRK were conducted by the NB65 hacking group, who took advantage of leaked code that resulted in the division of the Conti hacker group after a disagreement among members over the gang’s pledged support to Russia.

Russia was also the target of 40% of all screen-locking ransomware incidents (11% in Ukraine). Not surprisingly, just like we saw with the HermeticRansom display of political messaging, some of these attacks in Russia included the Ukrainian national salute, “Slava Ukraini” (“Glory to Ukraine”).

Exploiting fear and solidarity

It is not just the countries involved in the war that saw a spike in spam detections, mainly on February 24 and a total increase of 5.8% until April. Just after the war started, ESET warned of the danger of scammers shamelessly exploiting the worldwide movement in support of Ukraine with fictitious charities and false appeals for donations.

And as the war was leaving Ukrainians worried about accessing their money, or Russians abroad not being able to use their bank cards, ESET found increased targeting of cryptocurrency platforms and the spread of crypto-related malware.

Conclusion

The latest ESET Threat Report, released last Thursday, shines a light on the threat landscape in the first four months of this year. Above all, however, the attacks described show the destructive potential of cyberwarfare in parallel with a conventional, kinetic war. At the same time, the increased cyberthreats faced by Ukraine since January are also a warning sign about an escalation in future conflicts.

As ESET Senior Detection Engineer Igor Kabina observes, “We expect attacks supporting a particular side to continue in the upcoming months and even escalate as ideology and war propaganda are becoming the central driving forces for their spread.”