The old adage of people being the weakest link in security is especially true when it comes to email threats. Here, cybercriminals can arguable generate their biggest “bang for the buck” by socially engineering targets into following their instructions. Phishing is the most obvious example of such efforts, and there is one specific type of cybercrime that often leverages targeted phishing messages and has been the highest grossing of any criminal activity over the past few years: business email compromise (BEC).

The latest FBI Internet Crime Report reveals that, once again in 2021, these scams generated more losses for victims than any other type of cybercrime. It’s long past time that organizations got a handle on BEC and developed a layered defensive approach to mitigate the risk of losing large sums of money to faceless fraudsters.

How bad is BEC?

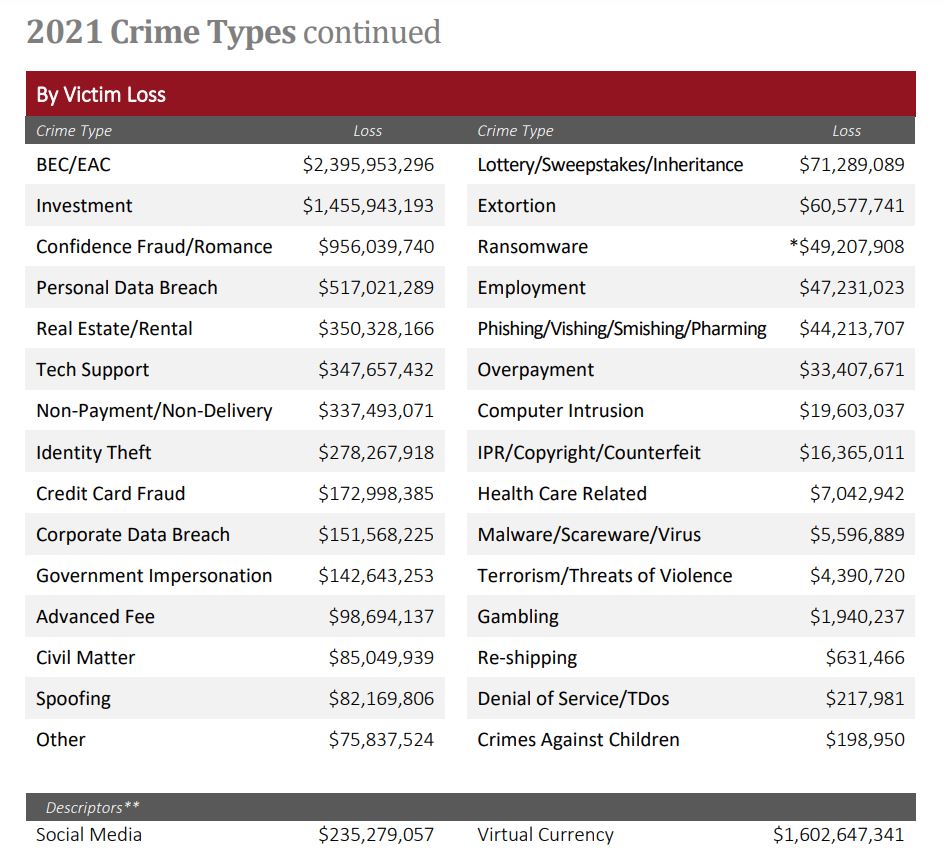

According to the aforementioned report, drawn up by the FBI’s Internet Crime Compliance Center (IC3), the IC3 received 19,954 BEC complaints last year. That actually makes it only the ninth most popular crime type of the year, far behind the leaders phishing (324,000), non-payment/non-delivery (82,000) and personal data breach (52,000). However, off the back of those nearly 20,000 BEC reports, scammers made an astonishing US$2.4 billion – far ahead of second and third-placed investment fraud (US$1.5 billion) and romance fraud (US$950 million).

That means BEC accounted for around a third (35%) of total cybercrime losses in 2021. This is actually a reduction from nearly half the year prior, but still represents an increase of 82% in real terms. It’s also true that in 2019, when BEC losses were around US$1.8 billion, the number of reports to the FBI was almost 24,000. So fraudsters are making more money off fewer attacks. How so?

How does BEC work?

They have certainly refined their tactics over the years. At a simple level, BEC is a type of social engineering. Finance team members are usually targeted by whom they believe to be a senior executive or CEO who wants an urgent money transfer to happen, or potentially a supplier that requires payment. Some demand wire transfers, while others ask that the victim buys gift cards and shares the relevant info with them.

As implausible as it sounds, these scams occasionally still work, because the victim is usually pressured to act, without being given time to think through the consequences of their actions – classic social engineering. And it only needs to work occasionally to make it worth the while of a fraudster.

A more sophisticated modus operandi will see the scammer first hijack a corporate inbox via a simple phishing attack. They may spend the next few weeks gathering intelligence about suppliers, payment schedules and invoice layouts. At the right moment, they’ll then step in with a fake invoice that requires the victim organization pay a usual supplier but with updated bank details.

Because these attacks do not use malware, they’re harder for organizations to spot – although machine-learning-powered email security is getting better at detecting suspicious behavioral patterns, to indicate a sender may have been spoofed. User awareness training and updated payment processes are therefore a critical part of layered BEC defense.

RELATED READING: 4:15 p.m.: An urgent message from the CEO

What the future holds

The bad news for network defenders is that the scammers are still innovating. The FBI warned that deepfake audio and video conferencing platforms are being used in concert to deceive organizations. First, the scammer hijacks the email account of a high-profile employee like a CEO or CFO, and invites employees to join a virtual meeting. The report continues:

“In those meetings, the fraudster would insert a still picture of the CEO with no audio, or a ‘deepfake’ audio through which fraudsters, acting as business executives, would then claim their audio/video was not working properly. The fraudsters would then use the virtual meeting platforms to directly instruct employees to initiate wire transfers or use the executives’ compromised email to provide wiring instructions.”

Deepfake audio has already been used to devastating effect in two standout cases. In one, a British CEO was tricked into believing his German boss requested a €220,000 money transfer. In another, A bank manager from the UAE was conned into transferring US$35 million at the request of a ‘customer.’

This kind of technology has been with us for a while. The concern is that it’s now cheap enough and realistic enough to trick even expert eyes and ears. The prospect of spoofed video conferencing sessions not only using deepfake audio but also video, is a worrying prospect for CISOs and risk managers.

What can I do to tackle BEC?

The FBI is doing its best to disrupt BEC gangs where they operate. But given the huge potential profits on offer, arrests will not deter cyber-criminals. Law enforcement will always be a game of whack-a-mole. More encouraging are the efforts of the IC3’s Recovery Asset Team (RAT) which claimed to have acted on 1,726 BEC complaints last year involving domestic-to-domestic transactions, and blocked payments of around US$329 million – a 74% success rate.

The challenge is that most BEC attacks will use bank accounts outside the US. In truth, the IC3 RAT recovered less than 14% of the total US$2.4 billion in BEC losses last year.

That’s why prevention is always the best strategy. Organizations should consider the following:

- Invest in advanced email security that leverages machine learning to discern suspicious email patterns and sender writing styles

- Update payment processes so that large wire transfers must be signed off by two employees

- Doublecheck any payment requests again with the person allegedly making the request

- Build BEC into staff security awareness training such as in phishing simulations

- Keep updated on the latest trends in BEC and be sure to update training courses and defensive measures accordingly

Like any fraudsters, BEC actors will always go after low-hanging fruit. Organizations that make themselves a harder target will hopefully see opportunistic scammers turn their attention elsewhere.