Editor’s note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of WeLiveSecurity and ESET.

This is probably not the first place one would expect to read about John McAfee; he had left the world of computer viruses behind a long time ago for more controversial pursuits; however, he was a person who was fundamental in shaping the computer security industry. More importantly to me, he was the person who gave me my first job right out of high school when I was just 19 years old, and was my mentor and my friend. I think, or at least hope, this entitles me to share some words about him here on WeLiveSecurity. If you are used to coming here for practical advice on how to protect your computer, or read about the latest advanced computer threat, thank you for indulging me.

For those who are somehow unaware, news has spread around the world that John apparently committed suicide in his prison cell in Spain. He was being held by the authorities there after being wanted for alleged financial crimes in the United States. Just hours before his death, the Spanish judiciary ruled that his extradition to the United States could proceed.

A lot of people I have known over the years, friends from far away and near, have been reaching out to me to share their condolences.

My feelings are conflicted. It seems like alternating waves of numbness and sadness would be the best description of them.

The web is full of places where I have discussed my time working for John across his various enterprises, both more formally here on WeLiveSecurity, and on places like Reddit where more informal conversations are the norm.

I am not really sure where to start with this, so I guess I should begin at the beginning, with how I met John.

Meeting John McAfee

It was 1985, and I was one of those uncool kids in high school, interested in computers, D&D, science fiction books and movies, and all the other things that while cool now, left one branded as a pariah and nerd. My escape was into the fledgling online world of bulletin board systems (BBSes), the precursor of today’s web forums and social media.

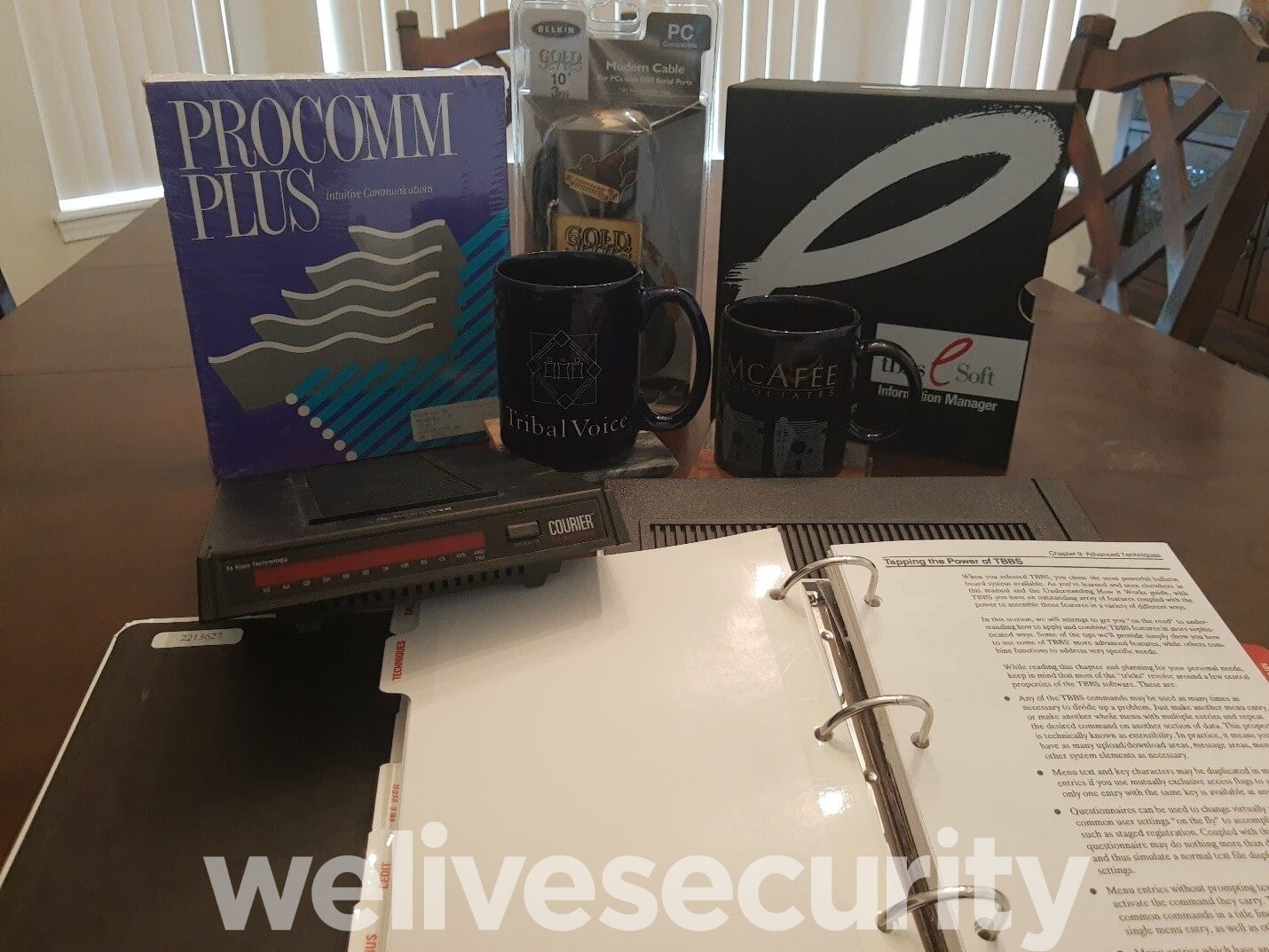

One of those BBSes I used to dial into with my modem was the Homebase BBS in Campbell, California, simply because it was a free call from where I lived in San Jose, right next door. Many BBSes had time limits for how long you could spend on them in order to free up their modem for the next caller, as well as strict upload/download ratios to prevent file leeches (people who downloaded files but never uploaded them, a parallel that might be familiar to users of today’s P2P software). Homebase was more generous than most with both. This was all pre-internet, or at least before the world-wide web took off, and BBSes tended to be local and could only support as many simultaneous users as they had phone lines, more often than not just one or two.

A notice appeared on the BBS one day that it was under new ownership. John McAfee, one of its users, had purchased it from the owner and moved it, computers, modems, phone lines and all, to the converted farmhouse he rented on Cheeney Street in Santa Clara. This was several years before he had started his eponymous company, McAfee Associates, that dealt with computer viruses. At the time, McAfee’s day job was as an engineer at Lockheed Missiles and Space Company in nearby Sunnyvale, CA, so this was very much a side business for him.

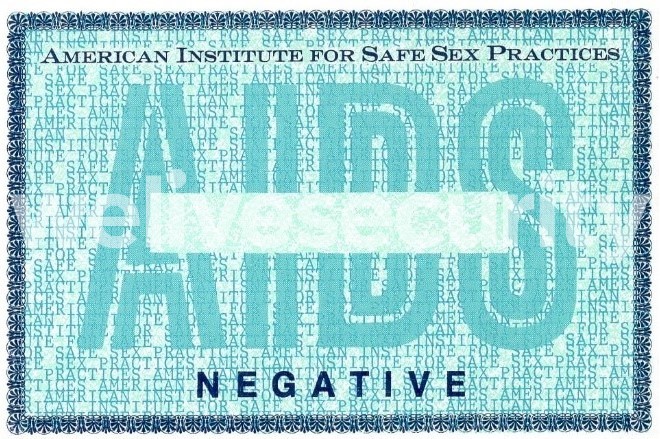

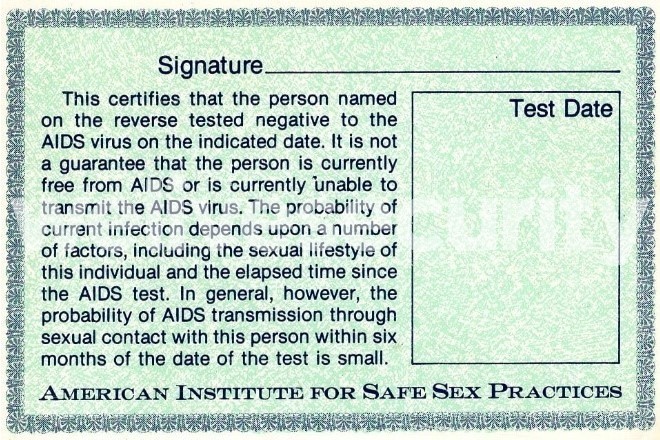

John’s purchase of the BBS was part of a plan to start a trade group for sysops (system operators; the people who ran BBSes), called the National BBS Society (NBBSS). When I met him, he had other businesses on the side as well, ranging from the American Institute for Safe Sex Practices (AISSP), which provided cards noting when the bearer had taken an STD test and that they were HIV-negative at that point (which has some interesting parallels to COVID-19 vaccination status today), to selling a sound card for PCs that was input only (e.g., it only had a connection for a microphone, not speakers). This was about a decade before sound cards were integrated into PC mainboards, and it had a small but dedicated base of customers for it, ranging from blind computer users who used it for voice recognition to a university in Hawaii that had purchased several of them for collecting dolphins’ “speech” using an array of underwater microphones. Some of those early audio card users became McAfee’s first customers for his antivirus software. As a result of that, we worked to ensure that the antivirus software was compatible with text-to-speech readers, Braille keyboards and other assistive devices.

Figure 2. A card from the American Institute for Safe Sex Practices – front (left) and back (right)

Today we call such things “side hustles” and they are recognized as part of the “gig economy.” To my teenaged mind, they were all very entrepreneurial-sounding and it was clear John had all his irons in the fire, any one of which might be the next big success.

None of these ever did take off, but his purchase of Homebase BBS led to his hosting of pizza parties for its users, and I finally got to meet him in person in 1986, after a year of dialing into the BBS. A number of us users became early employees, too.

John had a finely-tuned sense of what was and was not working for him, and with the AISSP and NBBSS businesses failing to gain any kind of critical momentum, he began to wind them down, along with the sound card business.

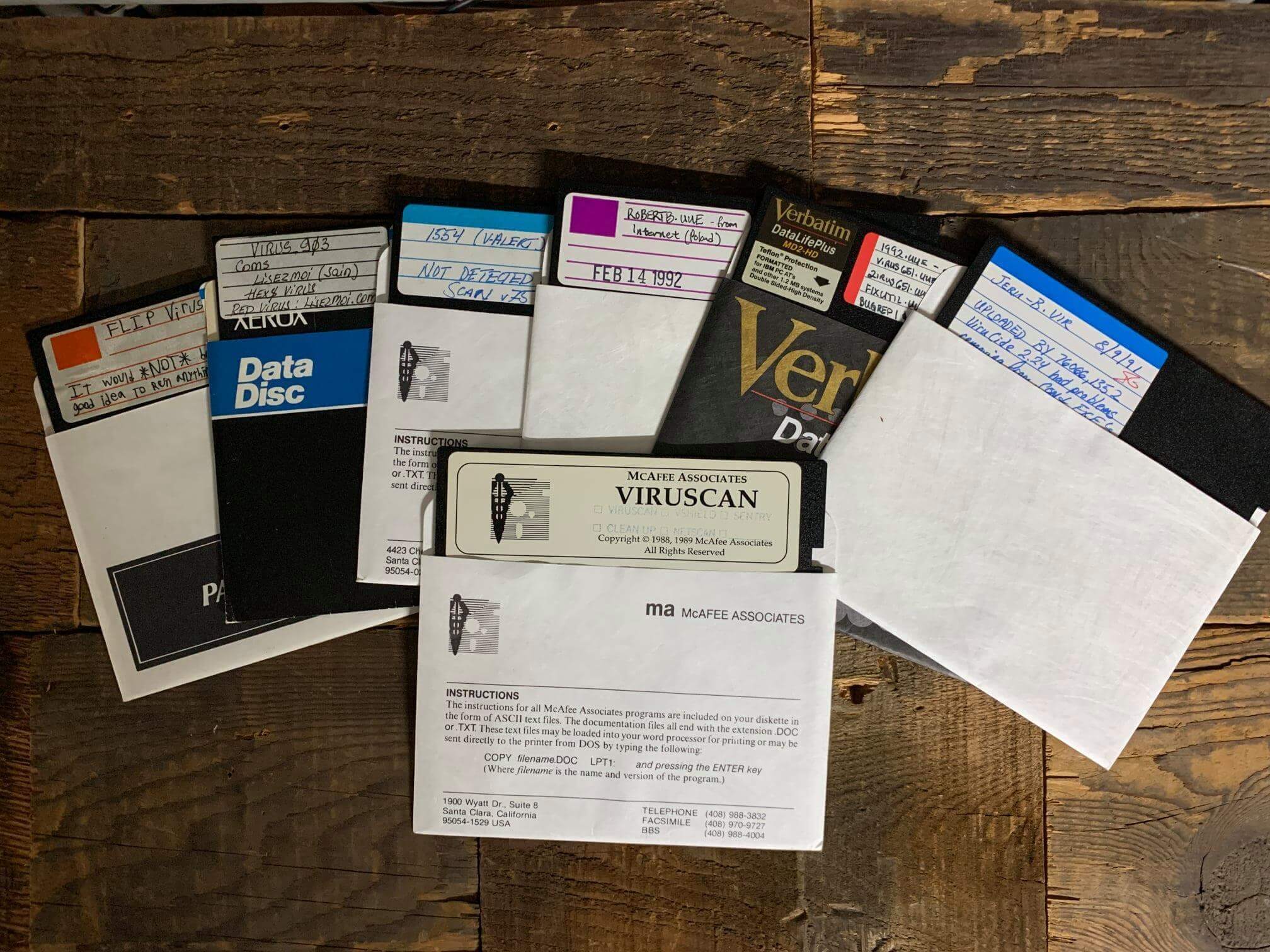

For his next side hustle, he took on antivirus software, distributing it online as shareware through the Homebase BBS. Shareware was a kind of honor system for software where people could try it out before making a purchase. In McAfee’s case, people could use the software for thirty days, and then either remove it from their computers or pay for it. This applied to organizations, too, who would have to purchase a site license if they wished to continue using the software. While downloading trial versions of software is the norm these days, back then, software was sold commercially in shrink-wrapped boxes on store shelves, and this was something of a gamble. Mr. McAfee did not invent the shareware business model or antivirus software, but he was the first to popularize them.

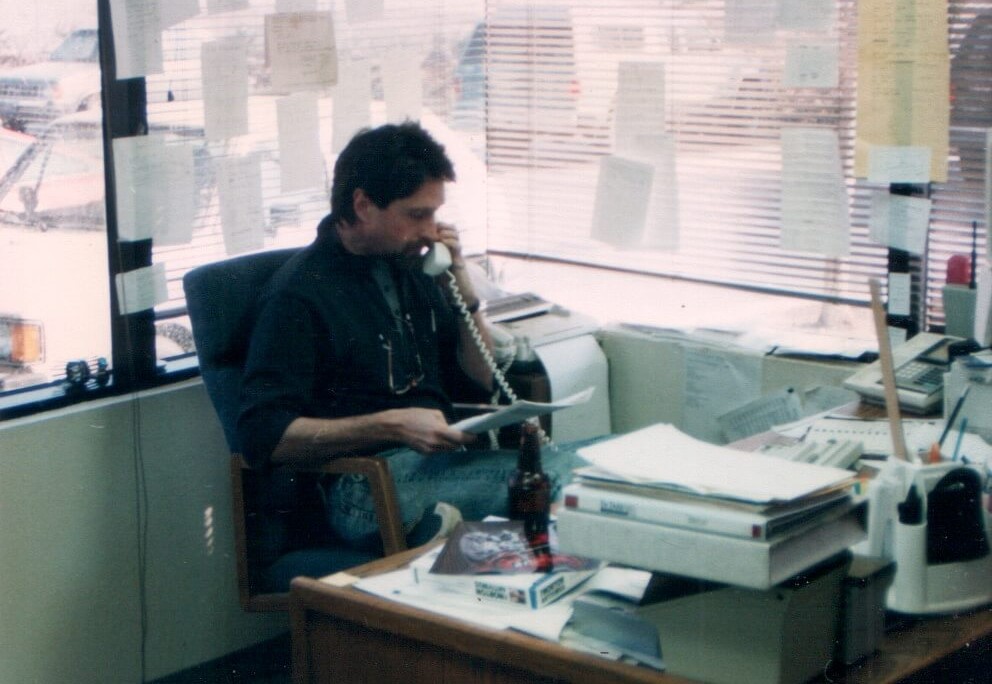

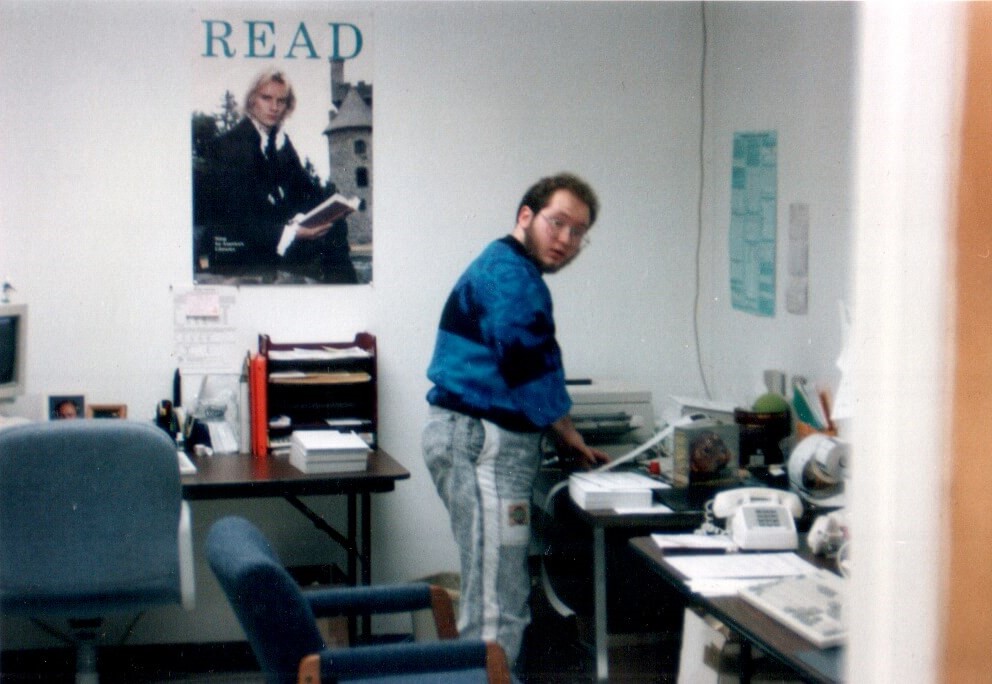

The first inkling I had that this was going to be any different from Mr. McAfee’s previous business ventures was when he appeared on the local TV news, talking about the Morris worm. A few months later, he appeared again, this time talking about the DataCrime computer virus. To nineteen-year-old me, fresh out of high school, studying cultural geography at the local community college and completely unsure of what I wanted to do with my life, this seemed like a golden opportunity: I asked Mr. McAfee if I could come work for him, perhaps to answer the phone, type letters and send faxes (tasks I knew well from working for my parents) and, to my surprise (and good fortune), he hired me on the spot.

I stayed with John as the company grew, first out of his house and then through a series of office parks. I grew, too, and ended up running all of the company’s support, writing all of the documentation, setting up the first quality assurance department and wearing all sorts of different hats that one needs to wear when working at a rapidly growing business. I ended up taking over running of the BBS from Mr. McAfee as well, becoming its sysop.

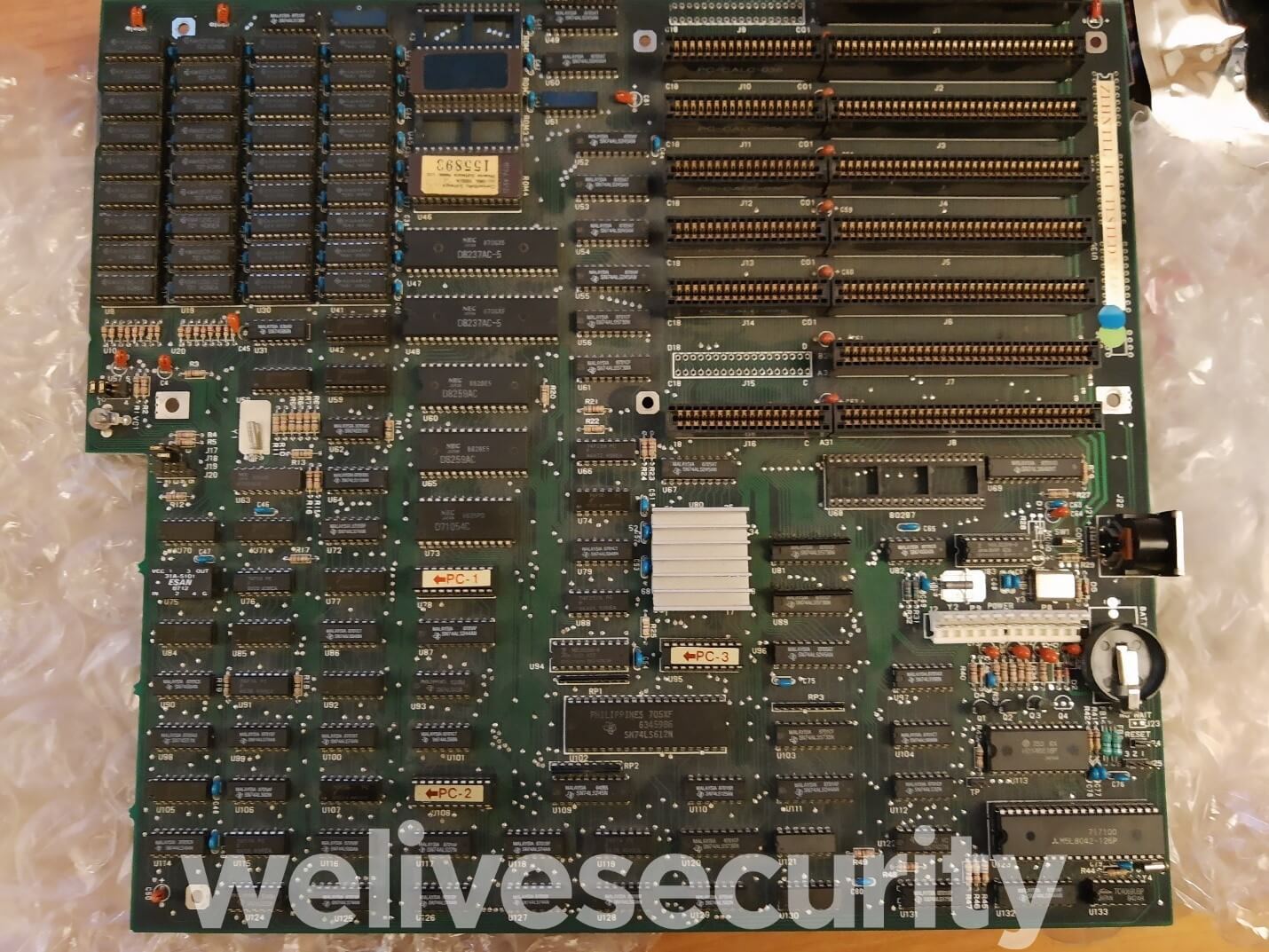

Figure 3. The 80286 CPU-based mainboard that powered Homebase BBS. It provided downloads of antivirus software, technical support and also allowed people to upload suspicious files. Basically, it was the web server of its era.

Figure 4. Floppy disks containing McAfee antivirus software and various virus samples. (Photograph copyright Dave Johnson. Used with his kind permission.)

The many faces of John McAfee

You may wonder what kind of person John McAfee was – before he became (in)famous for other things, anyway. There are some links at the beginning about my earliest experiences working for John, but those were written largely to capture moments I did not want to see lost, and do not define the man. So, what was he really like?

Mr. McAfee could be kind. There were numerous times when he stopped to perform small acts of charity, ranging from giving a homeless person some spare change, to just talking with them. Not mocking them, or being cruel. Just talking or, often enough, just listening.

Mr. McAfee could be mercurial. We would get into shouting matches, often, over the direction of something in one of the programs. They were usually over as quickly as they started, and no hard feelings afterwards.

Mr. McAfee was very intelligent. He could rapidly take in all sorts of disparate knowledge, synthesize it, and rapidly make a plan, figure out a solution to a problem, or come up with an idea. Sometimes he was wrong, but more often than not he was right. His ability to respond quickly, without hesitation, made the early McAfee Associates nimble and able to outpace competitors.

Mr. McAfee was often very unwise. While his business acumen was unparalleled, his personal life was… well “messy,” for lack of a better term. Unlike at other points in his life, at the time I met him, and throughout the time I worked for him, he was clean and sober. For anyone who plays D&D, I would describe him as INT 18, WIS 3. He could use his intelligence to extract himself from most situations, but kept getting into them, nonetheless.

Mr. McAfee could be charismatic. While he was leading McAfee Associates (and later, Tribal Voice, the instant messaging company he founded in Colorado), he inspired all of us, his employees. We worked hard and believed in the goal, whether it was saving the world from computer viruses, or trying to help connect the world over the internet.

Mr. McAfee could be kind of a d*ck, sometimes. He often took a “business is war” approach to the competition, relying on intellect to outmaneuver his perceived foes. That approach worked at early McAfee Associates, but didn’t scale in an industry where relationships had to be built on trust and cooperation.

Figure 5. Early days at McAfee Associates, circa 1990. Pictured are John McAfee (left) and this article’s author (right). (Photographs copyright Morgan R. Schweers. Used with his kind permission. The full album is available on Flickr.)

John McAfee lived a complicated and controversial life, accumulating many rumors and accusations around him. Many of them were true, but just as many of them were false. The funny thing is, some of the worst things said about him fell into the latter category: Stories about his either writing computer viruses, or paying others to do so, were false; no such thing ever happened while I was there. There were claims that he had hyped up the Michelangelo computer virus – but we had tallied up something like 60,000 infections before it activated in 1992, and McAfee Associates was only one of many antivirus companies back then, and certainly not the largest. That doesn't sound very hype-like, at least given the numbers for the state of antivirus in the early 1990s.

John took a leave of absence from McAfee Associates in 1993, which became permanent in 1994. At the end of 1994, he started Tribal Voice in Woodland Park, Colorado, which made some of the first instant messaging programs (IM) out there. What is interesting about Tribal Voice is that many of the features taken for commonplace in today’s IM software were created in that quiet little mountain town, such as using an email address for a username, and mapping that to an IP address so that messages could be sent to and fro. Given the rise of instant messaging and social networking, John’s impact in that space was as large as – or larger – than his impact in the antivirus space. Sadly, Tribal Voice was not a commercial success and the company went under when the dot-com bubble burst in 2001. That would mark the last time John McAfee helmed a tech company, although he was active as a financier and paid spokesperson for many others.

We had stayed in touch over the years and I even provided him with some technical assistance when he left Belize in 2012 and returned to the United States. He was rather insistent that I help various ghost writers ghost‑write his autobiography, but I demurred citing the amount of time it would require, and the fact that he did not want to pay me for it. We last talked during his 2016 Presidential campaign.

John McAfee was someone who very much lived life on his own terms, and I think that meant ending it on his own terms as well. Although he was an a**hole to me at times, he was also my friend, and he will be greatly missed.

Special thanks to my colleagues Tony Anscombe, Ranson Burkette, Bruce P. Burrell, Nick FitzGerald, Tomáš Foltýn, Rebecca Kiely, James Rodewald, James Shepperd and Righard Zwienenberg for not just the usual grammatical assistance but their moral support while writing this.

Aryeh Goretsky, ZCSE, rMVP

Distinguished Researcher, ESET

Title photograph copyright: Morgan R. Schweers. Used with his kind permission.