At the end of last year, we discovered targeted attacks against aerospace and military companies in Europe and the Middle East, active from September to December 2019. A collaborative investigation with two of the affected European companies allowed us to gain insight into the operation and uncover previously undocumented malware.

This blogpost will shed light on how the attacks unfolded. The full research can be found in our white paper, Operation In(ter)ception: Targeted attacks against European aerospace and military companies.

The attacks, which we dubbed Operation In(ter)ception based on a related malware sample named Inception.dll, were highly targeted and clearly intent on staying under the radar.

To compromise their targets, the attackers used social engineering via LinkedIn, hiding behind the ruse of attractive, but bogus, job offers. Having established an initial foothold, the attackers deployed their custom, multistage malware, along with modified open-source tools. Besides malware, the adversaries made use of living off the land tactics, abusing legitimate tools and OS functions. Several techniques were used to avoid detection, including code signing, regular malware recompilation and impersonating legitimate software and companies.

According to our investigation, the primary goal of the operation was espionage. However, in one of the cases we investigated, the attackers attempted to monetize access to a victim’s email account through a business email compromise (BEC) attack as the final stage of the operation.

While we did not find strong evidence connecting the attacks to a known threat actor, we discovered several hints suggesting a possible link to the Lazarus group, including similarities in targeting, development environment, and anti-analysis techniques used.

Initial compromise

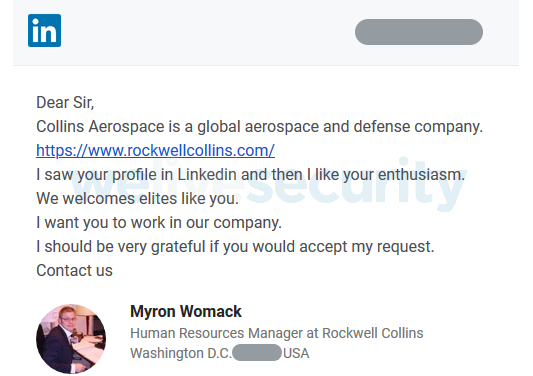

As part of the initial compromise phase, the Operation In(ter)ception attackers had created fake LinkedIn accounts posing as HR representatives of well-known companies in the aerospace and defense industries. In our investigation, we’ve seen profiles impersonating Collins Aerospace (formerly Rockwell Collins) and General Dynamics, both major US corporations in the field.

With the profiles set up, the attackers sought out employees of the targeted companies and messaged them with fictitious job offers using LinkedIn’s messaging feature, as seen in Figure 1. (Note: The fake LinkedIn accounts no longer exist.)

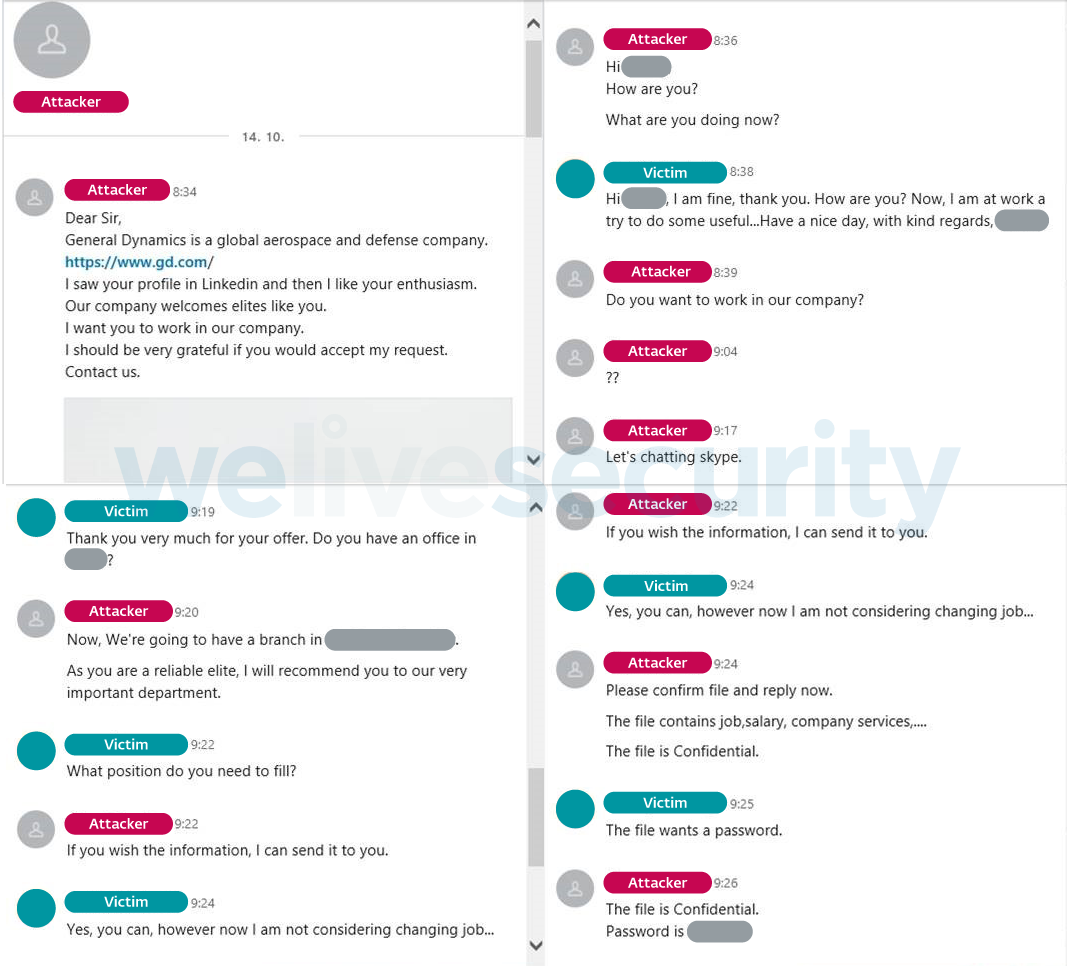

Once the attackers had the targets’ attention, they snuck malicious files into the conversation, disguised as documents related to the job offer in question. Figure 2 shows an example of such a communication.

To send the malicious files, the attackers either used LinkedIn directly, or a combination of email and OneDrive. For the latter option, the attackers used fake email accounts corresponding with their fake LinkedIn personas, and included OneDrive links hosting the files.

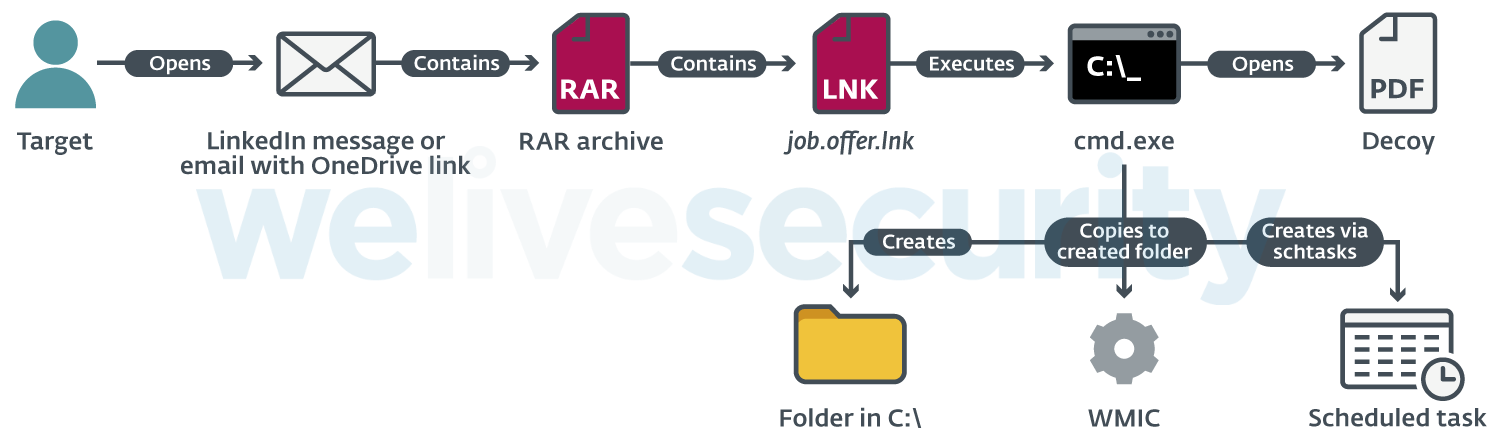

The shared file was a password-protected RAR archive containing a LNK file. When opened, the LNK file started a Command Prompt that opened a remote PDF file in the target’s default browser.

That PDF, seemingly containing salary information for the reputed job positions, in reality served as a decoy; in the background, the Command Prompt created a new folder and copied the WMI Commandline Utility (WMIC.exe) to this folder, renaming the utility in the process. Finally, it created a scheduled task, set to execute a remote XSL script periodically via the copied WMIC.exe.

This enabled the attackers to get their initial foothold inside the targeted company and gain persistence on the compromised computer. Figure 3 illustrates the steps leading up to compromise.

Attacker tools and techniques

The Operation In(ter)ception attackers employed a number of malicious tools, including custom, multistage malware, and modified versions of open-source tools.

We have seen the following components:

- Custom downloader (Stage 1)

- Custom backdoor (Stage 2)

- A modified version of PowerShdll – a tool for running PowerShell code without the use of powershell.exe

- Custom DLL loaders used for executing the custom malware

- Beacon DLL, likely used for verifying connections to remote servers

- A custom build of dbxcli – an open-source, command-line client for Dropbox; used for data exfiltration

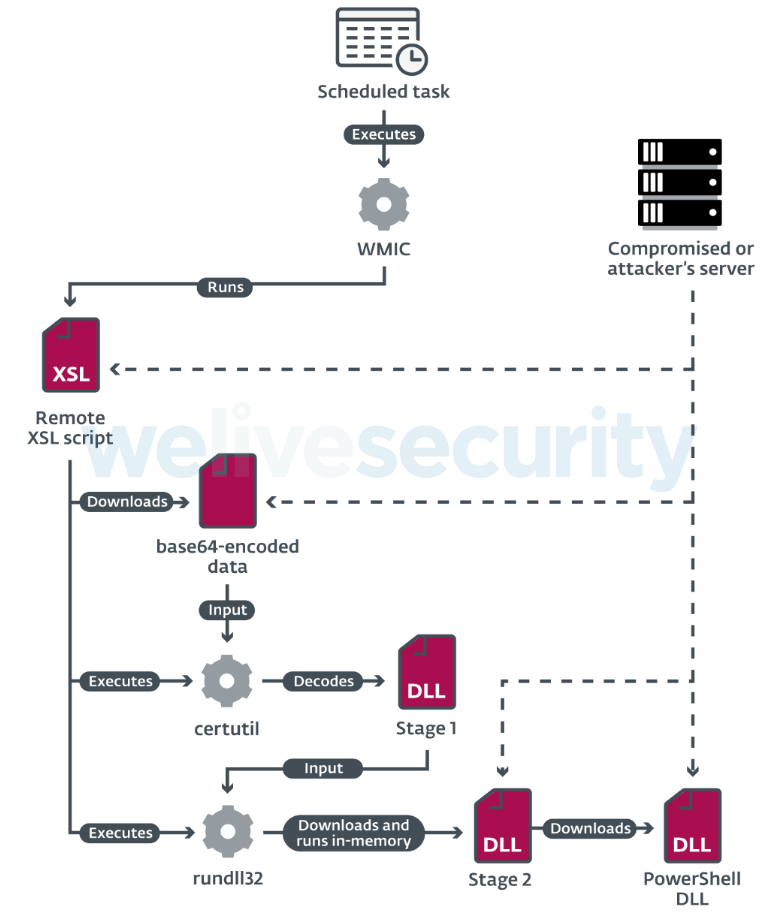

Under a typical scenario, the Stage 1 malware – the custom downloader – was downloaded by the remote XSL script (described in the Initial compromise section) and executed using the rundll32 utility. However, we also saw instances where the attackers used one of their custom DLL loaders to run the Stage 1 malware. The main purpose of the custom downloader is to download the Stage 2 payload and run it in its memory.

The Stage 2 payload is a modular backdoor in the form of a DLL written in C++. It periodically sends requests to the server and performs defined actions based on the received commands, such as send basic information about the computer, load a module, or change the configuration. While we didn’t recover any modules received by the backdoor from its C&C server, we did find indications that a module was used to download the PowerShdll.

Besides malware, the adversaries leveraged living off the land tactics, abusing legitimate tools and OS functions to perform various malicious operations, in an attempt to fly under the radar. As for specific techniques, we found that the attackers used WMIC to interpret remote XSL scripts, certutil to decode base64-encoded downloaded payloads, and rundll32 and regsvr32 to run their custom malware.

Figure 4 shows how the various components interacted during the malware’s execution.

Besides the living off the land techniques, we found that the attackers made special effort to remain undetected.

First, the attackers disguised their files and folders by giving them legitimate-sounding names. For this purpose, the attackers misused the names of known software and companies, such as Intel, NVidia, Skype, OneDrive and Mozilla. For example, we found malicious files with the following paths:

- C:\ProgramData\DellTPad\DellTPadRepair.exe

- C:\Intel\IntelV.cgi

Interestingly, it was not just malicious files that were renamed – the attackers also manipulated the abused Windows utilities. They copied the utilities to a new folder (e.g. C:\NVIDIA) and renamed them (e.g. regsvr32.exe was renamed to NvDaemon.exe)

Second, the attackers digitally signed some components of their malware, namely the custom downloader and backdoor, and the dbxcli tool. The certificate was issued in October 2019 – while the attacks were active – to 16:20 Software, LLC. According to our research, 16:20 Software, LLC is an existing company based in Pennsylvania, USA, incorporated in May 2010.

Third, we found that the Stage 1 malware was recompiled multiple times throughout the operation.

Finally, the attackers also implemented anti-analysis techniques in their custom malware, such as control-flow flattening and dynamic API loading.

Data gathering and exfiltration

According to our research, the attackers used a custom build of dbxcli, an open-source command-line client for Dropbox, to exfiltrate data gathered from their targets. Unfortunately, neither the malware analysis nor the investigation allowed us to gain insight into what files the Operation In(ter)ception attackers were after. However, the job titles of the employees targeted via LinkedIn suggest that the attackers were interested in technical and business-related information.

Business email compromise

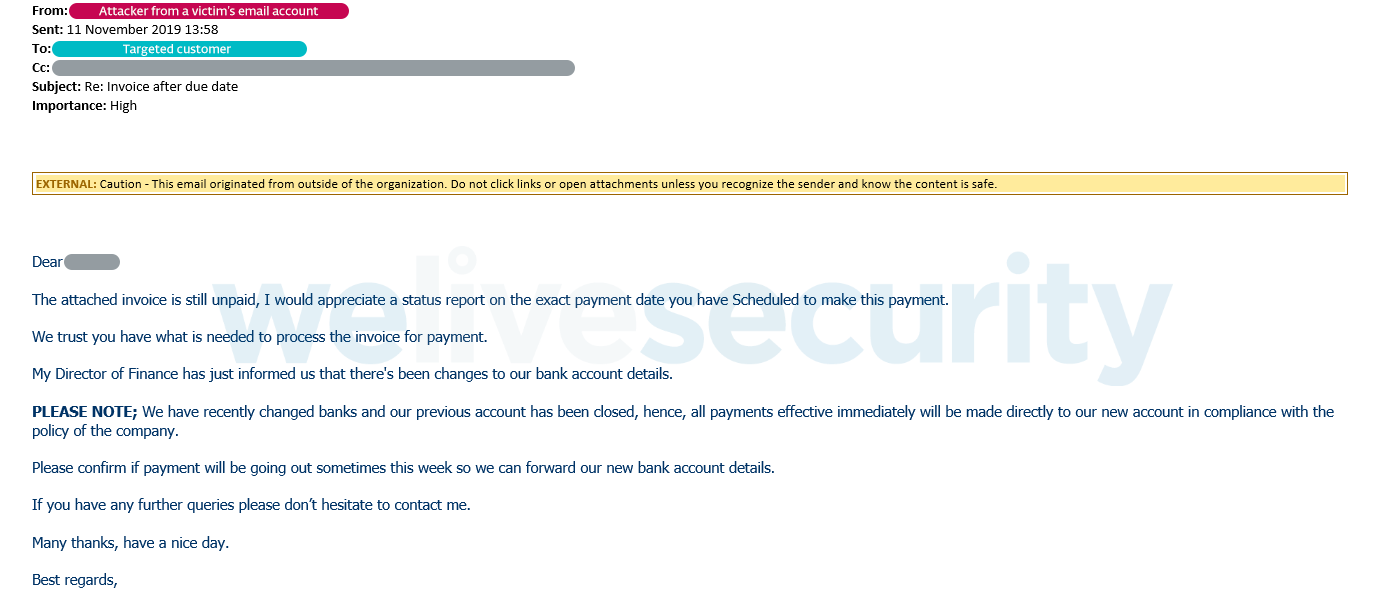

In one of the investigated cases, the attackers didn’t just stop at data exfiltration – as a final stage of the operation, they attempted to monetize the access to a victim’s email account through a BEC attack.

First, leveraging existing communication in the victim’s emails, the attackers tried to manipulate a customer of the targeted company to pay a pending invoice to their bank account, as seen in Figure 5. For further communication with the customer, they used their own email address mimicking the victim’s.

Here, the attackers were unsuccessful – rather than paying the invoice, the customer responded with inquiries about the requested sum. As the attackers urged the customer to pay, the customer ended up contacting the victim’s correct email address about the issue, raising an alarm on the victim’s side.

Attribution hints

Although our investigation didn’t reveal compelling evidence tying the attacks to a known threat actor, we identified several hints suggesting a possible link with the Lazarus group. Notably, we found similarities in targeting, use of fake LinkedIn accounts, the development environment, and anti-analysis techniques used. Besides that, we have seen a variant of the Stage 1 malware that carried a sample of Win32/NukeSped.FX, which belongs to a malicious toolset that ESET attributes to the Lazarus group.

Conclusion

Our investigation uncovered a highly targeted operation notable for its compelling, LinkedIn-based social engineering scheme, custom modular malware and cunning detection evasion tricks. Interestingly, while Operation In(ter)ception showed all the signs of cyberespionage, the attackers apparently also had financial gain as a goal, as evidenced by the attempted BEC attack.

Special thanks to Michal Cebák for his work on this investigation.

For the full description of the attacks, as well as technical analysis of the previously undocumented malware and Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), please refer to our paper, Operation In(ter)ception: Targeted attacks against European aerospace and military companies.

IoCs collected from the attacks can also be found on the ESET GitHub repository.

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

| Tactic | ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1194 | Spearphishing via Service | LinkedIn is used to contact the target and provide a malicious attachment. |

| Execution | T1059 | Command-Line Interface | cmd.exe used to create a scheduled task to interpret a malicious XSL script via WMIC. |

| T1106 | Execution through API | Malware uses CreateProcessA API to run another executable. | |

| T1086 | PowerShell | A customized .NET DLL is used to interpret PowerShell commands. | |

| T1117 | Regsvr32 | The regsvr32 utility is used to execute malware components. | |

| T1085 | Rundll32 | The rundll32 utility is used to execute malware components. | |

| T1053 | Scheduled Task | WMIC is scheduled to interpret remote XSL scripts. | |

| T1047 | Windows Management Instrumentation | WMIC is abused to interpret remote XSL scripts. | |

| T1035 | Service Execution | A service is created to execute the malware. | |

| T1204 | User Execution | The attacker relies on the victim to extract and execute a LNK file from a RAR archive received in an email attachment. | |

| T1220 | XSL Script Processing | WMIC is used to interpret remote XSL scripts. | |

| Persistence | T1050 | New Service | A service is created to ensure persistence for the malware. |

| T1053 | Scheduled Task | Upon execution of the LNK file, a scheduled task is created that periodically executes WMIC. | |

| Defense Evasion | T1116 | Code Signing | Malware signed with a certificate issued for “16:20 Software, LLC”. |

| T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | certutil.exe is used to decode base64-encoded malware binaries. | |

| T1070 | Indicator Removal on Host | Attackers attempt to remove generated artifacts. | |

| T1036 | Masquerading | Malware directories and files are named as, or similar to, legitimate software or companies. | |

| T1027 | Obfuscated Files or Information | Malware is heavily obfuscated and delivered in base64-encoded form. | |

| T1117 | Regsvr32 | The regsvr32 utility is used to execute malware components. | |

| T1085 | Rundll32 | The rundll32 utility is used to execute malware components. | |

| T1078 | Valid Accounts | Adversary uses compromised credentials to log into other systems. | |

| T1220 | XSL Script Processing | WMIC is used to interpret remote XSL scripts. | |

| Credential Access | T1110 | Brute Force | Adversary attempts to brute-force system accounts. |

| Discovery | T1087 | Account Discovery | Adversary queries AD server to obtain system accounts. |

| T1012 | Query Registry | Malware has ability to query registry to obtain information such as Windows product name and CPU name. | |

| T1018 | Remote System Discovery | Adversary scans IP subnets to obtain list of other machines. | |

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | Malware has ability to gather information such as Windows product name, CPU name, username, etc. | |

| Collection | T1005 | Data from Local System | Adversary collects sensitive data and attempts to upload it using the Dropbox CLI client. |

| T1114 | Email Collection | Adversary has access to a victim’s email and may utilize it for a business email compromise attack | |

| Command and Control | T1071 | Standard Application Layer Protocol | Malware uses HTTPS protocol. |

| Exfiltration | T1002 | Data Compressed | Exfiltrated data is compressed by RAR. |

| T1048 | Exfiltration Over Alternative Protocol | Exfiltrated data is uploaded to Dropbox using its CLI client. | |

| T1537 | Transfer Data to Cloud Account | Exfiltrated data is uploaded to Dropbox. |