Threat cumulativity is a term I began to use in 2018 to refer to the tendency of new technologies to spawn new threats that add to old threats without displacing them. In this article I give some examples of what I mean by threat cumulativity, some thoughts on why I came up with this term, and suggestions as to how it might prove useful in getting to grips with digital security.

Yes, security is cumulative

A few years ago, someone asked me to give a talk on the top five or six things that I had learned since I started researching computer security back in the 1980s. The first thing that came to mind was this: security is cumulative. In other words: protecting information systems and the data they process requires anticipation of new threats while defending against old threats.

So I made a slide that said “security is cumulative” and I started to include it in my talks about what is now called cybersecurity or – my preferred term – digital security. Fortunately, my presentations had already evolved in a way that illustrated the cumulative nature of threats to information systems.

In recent years I’ve given numerous talks that stressed the need for businesses to grasp the true scale of the cybersecurity problem, specifically the way it has progressed from disgruntled teenagers in hoodies hunched over keyboards in dark basements to coordinated campaigns of villainy in cyberspace. One approach I use to make my point is showing screenshots of the markets that traffic in stolen data. I also diagram the structured activity behind the creation and execution of malware campaigns.

When I first took this approach I said things like: “Don’t think random teenagers in basements, think people who go to work every day to penetrate systems and steal data.” But then I realized that was a mistake. Why? Ethically-challenged young hackers in hoodies have not gone away. Some of the biggest names on the internet learned that in 2016 when the Mirai botnet went from attacking minecraft sites to taking down a major Domain Name System provider; the story of the perpetrators was covered in depth by Brian Krebs – himself a victim of Mirai and other teenage criminals.)

Clearly, there is a need to protect information systems from well-resourced cybercriminals exploiting the latest vulnerabilities, but at the same time it would be foolish to neglect the threat from random hacker wannabees who are short on clues about consequences. Likewise it would be irresponsible for an organization to neglect anti-ransomware measures just because of a rise in cryptomining (as reported last year under headlines like Why cryptomining is the new ransomware and Ransomware is so 2017).

What cumulativity means for security

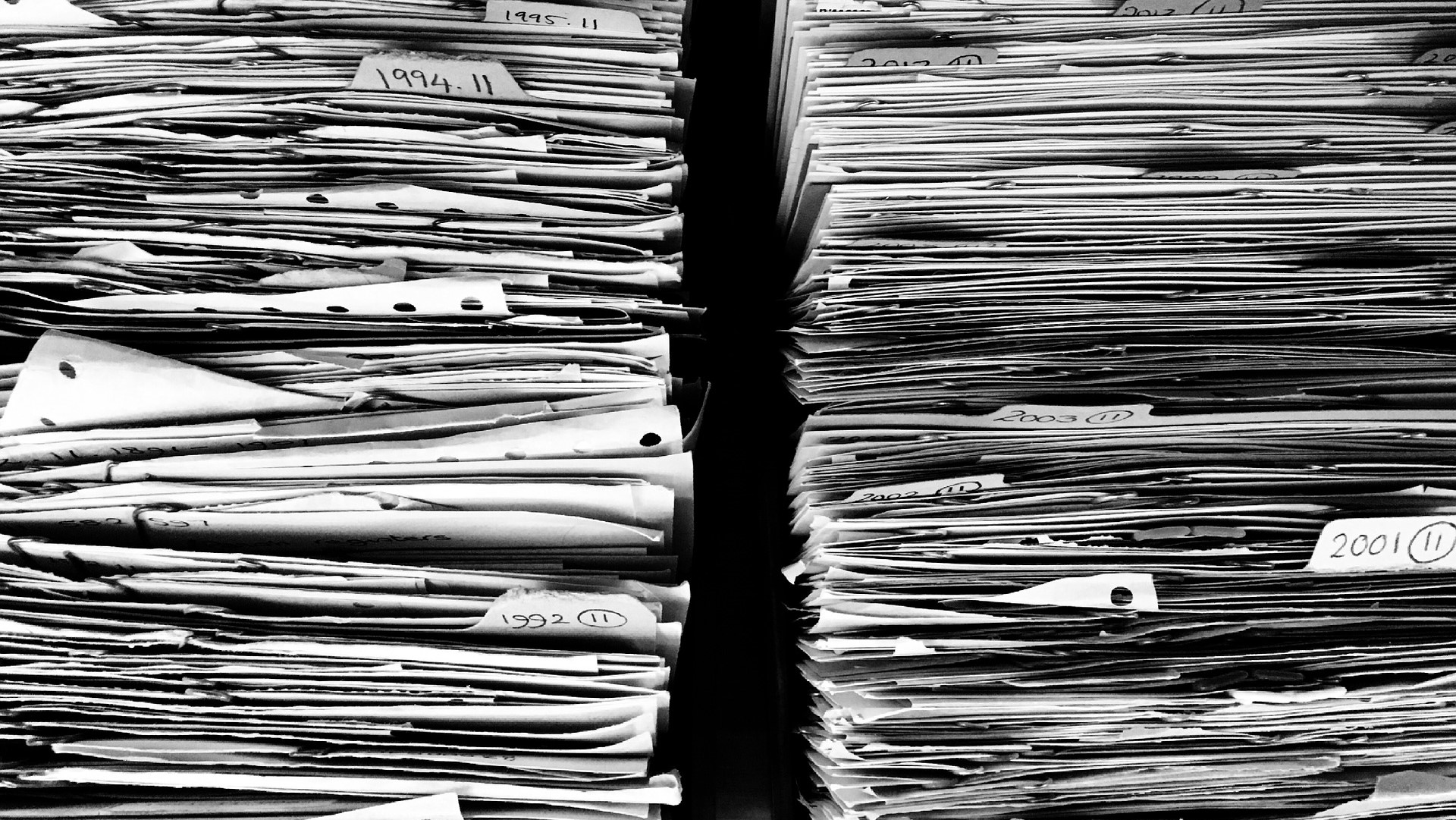

Security professionals have been dealing with the practical implications of threat cumulativity for decades. Once upon a time, computer security meant protecting a computer, a room-sized machine that usually lived behind locked doors. Threats back then included power supply issues, fire, flooding and other natural disasters. The main human threats were data entry errors or malicious code created by people authorized to use the computer, in other words: insiders. As computers got smaller and more numerous, more people learned how to use and abuse them, and the range of threats expanded to include theft of the computer and its components (the theft of an IBM PC was my first professional encounter with computer crime, circa 1986). At the same time, earlier threats like earthquakes persisted (one of my publishers lost many PCs due to overheating when the San Francisco earthquake of 1989 rendered its offices inaccessible and knocked out the air conditioning.)

The use of removable media – such as floppy disks – increased the viability of new threats like computer viruses and data theft. When the networking of computers started to happen, old threats like insider abuse and data theft were given fresh opportunities, even on small Local Area Networks or LANs. When organizations started to connect multiple offices over Wide Area Networks (WANs) then data and system access was exposed on wires that the organization itself could not protect. And of course the coming of “The Internet” took that problem to a whole new level.

Of course, at each step of the way, security professionals have warned that deploying new technology that is not “secure by design” will only add new threats to the already considerable security burden. About the middle of 2018, I articulated this aspect of threat cumulativity as a Twitter thread. Sadly, it did not “go viral,” but it did help me clarify my thoughts, so I want to share it here:

- For several years I have been using the phrase “security is cumulative” when briefing organizations on information security strategy. Here is how this comes about.

- Each step in the evolution of technology has prompted warnings about criminal abuse and unforeseen negative consequences. Many warnings go unheeded until incidents of abuse and negative consequences occur;

- at which point the problems are debated and measures to address them are drafted. Many of those measures are then ignored and the problem is talked down in some circles. While some measures may be implemented, it's too late or without enough resources to make a difference.

- The result is new threats, even as old threats persist. I propose we call this phenomenon the cumulativity of threats. Here is an example:

- People exploiting vulnerabilities in software are a threat to the security of your information, which is also threatened by people using phone calls to perpetrate support scams. In other words, threats permeate the technology stack, from the telephone to the latest software.

- Threat cumulativity has several important implications. Most obviously, you have to guard against old threats while thwarting new ones. But threat cumulativity also has serious implications for the future of technology.

- For example, I would argue that – unless we change the way we have been doing things – cumulativity will negatively impact the odds of humans achieving a net improvement in the quality of life from each new generation of technology.

Ever since I wrote that, I have seen a lot of confirmation that my observations are correct. Of course, there’s probably some confirmation bias at work, but consider a single 10-day chunk of information security news randomly sampled from 2018:

- One of the world’s largest makers of computer chips hit by virus

- FBI warns that IoT devices are being abused by criminals

- Malware delivered by snail mail, and yes, it's 2018

- Brute force attack hits medical testing firm with ransomware

- Bitcoin SIM card scam 'new way to commit old crime'

That’s five examples in 10 days, five headlines that reflect the reality that “security is cumulative”. While many information security professionals have, over the years, stressed the need to learn from history, I decided that this aspect of digital security – the need to defend against an accumulating list of threats – deserved a name, hence: threat cumulativity.

Helpful language?

I assume there will be some objections to the term “threat cumulativity”. Some will say "cumulativity is not a word" and "everybody knows this already." To the first point, cumulativity is a word, as I will explain in a moment. As for "everybody knows this already" let me clarify: if you are a security expert, you probably do know that threats are cumulative. But a whole lot of people whose work impacts security have not yet internalized the implications of this phenomenon. I think that having a term to describe the phenomenon will help to spread awareness of its implications.

As for cumulativity, it is a term used in linguistic semantics to describe an expression (X) for which the following holds: "If X is true of both of a and b, then it is also true of the combination of a and b” (Wikipedia). A commonly cited example is the expression “water”. If you combine two things that are water, what you get is more water. That said, I freely admit to not being an expert in linguistic semantics (although I do have a degree in English). Nevertheless, I think that adapting cumulativity to the security lexicon is a valid use of the word, one that can help people understand – and defend against – the phenomenon it purports to describe.

Another possible objection to "threat cumulativity” is that a better term might be “risk cumulativity." This is a non-trivial point and so I am going to address it in a separate article. That said, I think there are good strategic reasons for using "threat" here rather than "risk". However, I’d also like to hear what you think. Is the idea of threat cumulativity helpful? Do you see examples of this?