Sadly, most cybersecurity experts were not surprised to hear that there are serious vulnerabilities in the Uconnect infotainment system installed in 1.4 million vehicles manufactured by Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (also known as FCA). Those vehicles, which include cars and trucks branded Chrysler, Jeep, and Dodge, are now the subject of the world's first automotive cybersecurity recall, potentially tarnishing those bands and wiping millions from FCA's bottom line. This could become a classic study in how failure to adequately address cybersecurity risks during product development and deployment ends up costing a manufacturer millions of dollars.

Right now, across the United States, Chrysler/Jeep/Dodge are busy gearing up to handle this "cybersecurity recall" because next week, at the Black Hat security conference in Las Vegas, security researchers Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek will be presenting more details of the vulnerability, further raising awareness of the problem (although it may be hard for the media to top this headline from Fox News: "Patch your Chrysler vehicle before hackers kill you").

Why is this hack not surprising?

Human beings have a long history of deploying information technology that is inherently insecure, despite a constant litany of warnings from experts that this is not the best way to go about things; warnings like this very prescient piece from early 2012 by ESET researcher Cameron Camp. Why do we humans behave like this? I think there are several reasons, starting with our tendency to overlook the baser tendencies of our fellow creatures. The number of people prepared to profit at the expense of others may be higher than your typical upstanding member of society realizes. I think that helps explain why the healthcare industry, populated by doctors and nurses who go to work every day to help others, has not developed data security as quickly as other sectors.

An excessively sunny view of human being might also explain why some engineers fail to see what a devious delinquent might do with a technology that was designed to do good things. Cybersecurity in the manufacturing sector may also suffer, at times, from an excessive enthusiasm for technology that causes its downsides to be overlooked (as the son of an automotive engineer I remember my father extolling the benefits of asbestos for various projects, before we learned how hazardous it could be).

Another reason manufacturers may not see cybersecurity issues coming is that the digital world of cyberspace is very different from the physical world of meatspace. Even if you are an automotive engineer who is aware that some people do bad things, like drive drunk or steal cars--realities against which you work to protect people through product innovations, you may find it hard to visualize cyber threats. For example, how many vehicle entertainment system designers are aware that there's a global market in malicious hacking tools and people willing to use them? And by the way, those people include thieves, spies, nation states, law enforcement agencies, activists, and random grudge-holders, from every country on the planet.

Here's what is surprising

Although I was not surprised that there were vulnerabilities in the Uconnect system, I was surprised at how serious they were, and how casual FCA appears to have been about them. Here's what the company knew in January 2014: "A communications port was unintentionally left in an open condition allowing it to listen to and accept commands from unauthenticated sources....the radio firewall rules were widely open by default which allowed external devices to communicate with the radio."

So what did the company do with this information? It worked on some improvements that went into vehicles built after June of last year; but apparently it did not reach out to owners of vehicles that still had those issues until July 14 of this year. That's when the company decided to notify customers of "free software updates to all affected vehicle owners".

How do those "free" updates work, the ones that close the open port and fix the firewall? You have to go to a website and download a large disk image to a 4 gigabyte USB drive that you then plug into the infotainment system (drive not included). It is at this point that the Geek Chorus chimes in: "What could possibly go wrong?" Here are 10 suggestions, based on a population of 1.4 million people:

- Owner doesn't have an Internet connection.

- Owner's Internet connection can't handle 690 megabyte downloads.

Owner's computing device does not have a suitable USB port.

Owner's computing device does not have a suitable USB port.- Owner's device is infected with malware.

- Owner's USB drive is infected with malware.

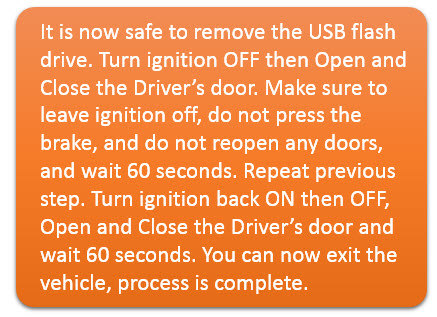

- Owner fails to complete instructions correctly (e.g. see image on right for step 10, the final stage of the update process, to gauge how easy this is).

- Owner clicks on an update download link in an email that looks like it came from Chrysler, but actually came from a criminal.

- Owner gets a phone call from Customer Care at Jeep offering to talk him through the update process, but it is not really Customer Care at Jeep that is calling.

- Owner is unknown or otherwise unreachable.

- Criminals examine the update files, which are freely available to the general public, to figure out new exploits.

If you did a double-take on this last point, let me explain: anyone can download the update file if they have a VIN from an affected vehicle (see this page). To get such a VIN you just search for an affected make/model in used car ads (which typically include the VIN so that buyers can check the vehicle history). It took me less than a minute to find a suitable VIN.

How do you fix vehicular insecurity?

So how should FCA solve this problem? Shortly after the fatality potential of the unpatched vulnerabilities was reported by WIRED, FCA announced a recall so that dealers could install the fix for customers. A recall is a much bigger deal for FCA than their original "free software update" plan of "sending all affected customers an email (where available) and a first class branded letter" with do-it-yourself instructions.

A recall has a special status in law and comes with legal obligations such as warranties (here is the specific recall page at chrysler.com). However, recalls are by no means perfect, as my Jeep-owning colleague Cameron points out: "Not everyone gets the notice. Not everyone acts on the notice. Vehicles age and change hands. Some vehicles are owned by rental companies who may not get round to the recall."

In other words, it is hard to see how you can effectively handle a critical vehicle software vulnerability without the ability to securely push the update to every vehicle, hopefully at about the same time (a classic technique for the malicious exploitation of software vulnerabilities is to target unpatched systems). So here is where the lessons of history come into play: the cybersecurity risks of vehicle software need to be addressed in the product development life cycle, and throughout the product life cycle. It now appears that FCA did not do a good job of this, leading me to wonder if there was a conversation at FCA along these lines:

- Adam: Let's enable the vehicle to receive commands remotely.

- Bob: How do we stop unauthorized people issuing commands?

- Chuck: We'll use a firewall.

- Bob: What if we find the firewall was misconfigured after the vehicle ships?

- Chuck: People can update the software.

- Bob: Which people, and where will they get the update?

- Chuck: Owners, off the Internet, with USB drives.

- Adam: Sounds good.

Well, it might have sounded good to Adam at the time, but in hindsight he was entirely wrong-headed, as any security professional would have been happy to point out, if there had been one at the meeting (and yes, there should have been one at the meeting, but no, those are not actual names of FCA employees, I just randomly assigned them).

Risks, rewards, and repercussions

How much would good security advice have saved on this radio design issue? A lot more than $10 million. Let's say one million out of the 1.4 million affected vehicles come in for the fix. According to Service Bulletin 08-031-15 REV.A the manufacturer is paying dealerships for 0.4 hours of work per vehicle to install the update. Assuming the warranty work is reimbursed to the dealer at $25 per hour, then just that part of the operation is going to cost $10 million (1,000,000 x 0.4 x 25). There is also the cost of informing owners of the problem, plus additional per dealer reimbursement for the software download time. (BTW, there is no word on who buys the USB drives, and the dealer needs two because there are two versions of the radio: see PDF of the bulletin here.)

Cynical readers may point to the past history of the automotive industry in which car companies have been known to sell cars that are known to be defective, based on a risk assessment that the cost of fixing the defects in production would be greater than the cost of the problems to which the defects give rise (even if those problems include injuries, fatalities, and lawsuits). That cynicism was probably reinforced this week by of US government action against FCA that predates the software issue: Fiat Chrysler was hit with the largest ever National Highway Traffic Safety Administration fine, and the basis of this was "lax attitudes towards addressing safety issues in millions of its vehicles" (Detroit Free Press). By some estimates, theremediation measures agreed to by FCA could cost the company more than $1 billion.

So, I will let Cameron have the last word, since he owns one of those Jeeps that is under recall for a faulty fuel tank: "A recall is much less effective than a patch that gets pushed. Think if you had to bring your computer in to have Microsoft install a patch. Sure, they’d pay for it, but the patch rate would be abysmal. The problem is that many automobiles aren’t set up to have an effective patch cycle, so they’ll have some catching up to do, and that’s just on newly sold automobiles. On top of that, while people may keep a computer for a few years, cars keep going for decades; so when would an automobile company declare ‘end of life’ for supporting legacy cars that are found to have hackable defects?”

Image info: 2001 Jeep Grand Cherokee photographed by the author in 2011, with added "custom" license plate (I owned the vehicle when the photo was taken, and had just driven it 3,000 miles from New York to San Diego, towing a large UHaul trailer).